Interview:2000/11/01 AP "Death Was Waiting At My Door"

| "Death Was Waiting At My Door" | ||

|---|---|---|

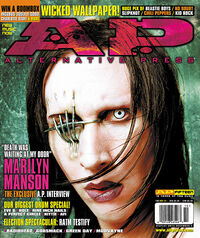

photo: Marina Chavez

|

||

| Interview with Marilyn Manson | ||

| Date | November 1, 2000 | |

| Source | altpress.com [1] nachtkabarett.com[2] |

|

| Interviewer | Tom Lanham | |

"Death Was Waiting At My Door"

MARILYN MANSON: The Exclusive A.P. Interview

HE RETREATED INTO THE SHADOWS

FOLLOWING COLUMBINE WITH

DEATH LOOMING AT HIS DOOR.

NOW HE’S BACK WITH-SURPRISE-

HIS DARKEST ALBUM EVER.

IN THIS EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW, MANSON REVEALS

HOW HE GATHERED STRENGTH AND

WISDOM IN HIS BLEAKEST HOUR

The goths truly believed

They had the inside track:

The goths were dead wrong.

In a backstage holding pen at San Francisco’s historic Cow Palace roughly a year a go, it was all streaked raccoon eyeliner, billowy black satin and velvet, and big Barnabas Collins-cool capes. And that was just what the boys were wearing; the female fans, nervously pacing alongside their spooky male counterparts, were dressed even more groovy-ghoulish. But everyone, it seemed had a story—a reason why they should be culled from the ho-hum herd and ushered upstairs to the dressing room, the sanctum sanctorum where HE sat holding court with a most privileged few. To what lengths would a determined death rocker go to meet his/her idol, that reigning king of industrial-strength shock, Marilyn Manson? Only his/her hair-dresser knew for sure.

Gabriel’s trumpet finally sounded-after nearly an hour, a management representative arrived with the sacred parchment, a scroll bearing the names of those who would be Charon-ferried to the mysterious other side. Eagerly, the 40-plus goths gathered in an omoeba-like black mass, a huge Baskerville beast hell-bent on over-taking its target. They leaned forward, waited as the few were called, waited, waited...

“Excuse me,” Coughed a pre-teen in geeky John Denver glasses, as he elbowed his way through the throng, “I think I heard my name.” a disgruntled murmur rumbled deep within the congregation. There were more awkward misfits to come. One one by one, like children of the corn, they trotted forward as they were summoned, all Reeboks, Gap khakis and goofy smiles. The goths were dumbfounded. Surely there must be some mistake! Their icon— no stranger to sartorial splendor himself—simply HAD to appreciate all the ruby-lipped, Cure-coiffured effort they’d undertaken just getting ready for his long-awaited Mechanical Animals concert! These nerdy little kids weren’t sporting anything even remotely Crypt-Keeperish in style, for Lugosi’s sake! But the mistake, sadly, was theirs and theirs alone.

The goths had sorely underestimated their idol, completely miscalculated the primal—and often rather heartwarming—forces that make him tick. The equation was tit-for-tat basic that night: The luck tadpoles were contest winners and their plus-ones, the most true-blue of Marilyn Manson acolytes who had, in a Web site-sponsored tournament, logged more successful radio-request calls than their competitors. Their meeting with the artist was no glad-handing photo op, either—Manson invited them all into a special suite (where many sat next to him on a red velvet couch, wide-eyed, studying his platform boots and leopard-print post-show casual wear) for a city hall-type chat. The kids got the chance to tell him what subject they enjoyed in school, how they felt about his concert that night and what educational plans they had for the future.

Never forced or fey, the get-together lasted nearly 15 minutes and ended in a friendly autograph-and-handshake farewell, one that would stun all those God-fearing, finger-pointing parents who’ve been swearing this man is the devil incarnate for all 10 years of his Grand Guignol-theatrical career. Eventually, the goths gave up and slithered home, the message pinging around their batcave brains: Manson isn’t fooled by foppish artifice. And he always takes care of his own.

Or, as this self-proclaimed Antichrist Superstar put it more recently, his lanky feline form draped gelatinously across his plush home studio sofa, “Spending time with those kids was not just me being magnanimous—it was just me really relating to them. Because I don’t know if there’s any artist who feels as much like his fans as I do, especially now that I’m so dejected and so looked down upon by so many people.” He pauses, just long enough for a rimshot punch line to crackle through. “Whose opinions I don’t really care for anyway. But I do have a backward sense of optimism, and my point is always to try and better mankind. I’m not just a nihilist or some doomsayer—I’m saying these things because they’re warnings, because I want humankind to not let it happen this way.”

Don’t sweat the small stuff, philosophers tell us. Don’t get lost in the minutiae. Then again, look at Achilles—one tiny imperfection in his impervious armor brought that warrior down. A few days after the Bay Area meet-and-greet in ’99, Manson was sipping an early-morning cocktail in his hotel room—Chicago, he thinks it was—when a breaking CNN news bulletin shatter his reverie: Two so-called “trench-coat mafia” youths, Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris from Columbine High in Littleton, Colorado, had undertaken a systematic slaughter of their classmates, a bloody bullet-riddled path that would lead straight to suicide for the misfit pair.

As he watched the report unfold, revealing the duo’s fascination with heavy industrial music, Manson remembers being struck by one key thought: “I’m going to get blamed for this.” And he was. Quite erroneously, of course—a Denver journalist let the way in uncovering the truth, that Klebold and Harris weren’t even into Manson; his more hook-conscious efforts were just too mainstream for their hardcore KMFDM tastes. Too late. From this one small seed of misinformation, a might gallows had grown. And the public was hungry for a hanging.

The Columbine tragedy isn’t one of the performer’s pet subjects; he’s got a new concept album he’s itching to discuss, Holy Wood (In The Shadow Of The Valley Of Death) the Episode Three in his Antichrist Superstar/Mechanical Animals trilogy (all on nothing/Interscope).

Additionally, a tandem novel will be published under the same name, and later—if all goes according to plan—the entire project will quantum leap to the silver screen. Meanwhile, Manson’s spooky chiseled-cheekbone visage can be seen flickering through the latest rock videos from fellow provocateurs Eminem (“The Way I Am”) and Nine Inch Nails (“Starfuckers, Inc,” mending an old rift with former friend and nothing mogul/mentor Trent Reznor, who’d initially penned the cut to mock Manson).

But you can’t reach Holy Wood without first respectfully visiting Colorado. The incident, Manson sighs, shaking his head, “was something that was very bad, and it had a lot of bad effects on everyone’s life. Obviously, I can’t sit here and say that my life was worse than the people’s who were directly involved in it, but being blamed and hated by so many people... I mean, how was I supposed to fight it? There wasn’t any way, because their accusations were incorrect, and there were too many emotions involved.”

KMFDM (now rechristened MDFMK) got off easy, Manson figures. “They didn’t have an image that was familiar to housewives. And Marilyn Manson is someone that—if you put me on the TV—I just look responsible. I look like the guy that you would blame. Which made it easy for the news to pine me up. It works in a pure marketing sense, because the news is just selling fear, and I’m a poster boy for that.”

As music, film, art itself was called into bad-influence question, every news outlet in the stratosphere wanted this wicked makeup-wearing miscreant pilloried for his supposed proxy involvement in the bloodbath. Or at least a few juicy exclusive quotes. Nolo contendre, responded Manson—he declined to comment. In retrospect, he see “the whole situation as being very emblematic of the name Marilyn Manson and why I created it. These kids [Klebold and Harris] were mad because they felt like they didn’t fit in and they wanted to show the world. And the world, in return, gave them exactly what they wanted—they put ‘em on the cover of Time magazine. Twice. That was disgusting to me.

“I said this same thing 10 years ago when I created Marilyn Manson—there’s a very fine line between an artist and a serial killer or a mass murderer. They’re both trying to get out the same feelings, and they’re doing it because they know that America is gonna put ‘em on the news—they enjoy the fame of it.”

Believe it or not, the maligned Manson actually felt a bead being drawn on his own skull as the post-Columbine tensions festered. He nutshells that foreboding feeling as ‘not a fear, but a knowledge—even a sense of paranoia, maybe. I mean, I didn’t physically leave my house for three months, and one reason why I didn’t leave was, I genuinely believe that there was a realistic possibility that I could be poisoned at a restaurant, or shot in a Mark Chapman style.”

He isn’t kidding. The threat wreaked havoc on his relationship with Rose McGowan; Manson’s long delicate fingers curl into stress-tight fist just talking about it. “I felt it, felt the stare—it was real. Death was waiting at my door, I really thought so. That’s why the [Mechanical Animals] tour ended. We were cancelled in a lot of places [mostly notably Denver], but I ended it for everyone’s safety—the fans’ and my own. There were just too many emotions involved, too many dangerous people out there. I thought America needed time to cool off.”

Afterwards, locked away in his Hollywood Hills garret, came a period of stark introspection for the hard-ridden rocker. “It was a time when I was trying to decide in some ways, if I was going to continue. And if so how? There was a bit of trepidation, deciding, ‘Is it worth it? Are people understanding what I’m trying to say? Am I even gonna be allowed to say it?’ Because I definitely had every single door shut in my face [after Columbine], more than most people would imagine. At the time that it was happening, there were not a lot of people who stood behind me.”

Manson’s pouty lips curl into a sinister snarl as he hisses, “But the ones who did will be remembered and rewarded and the ones who didn’t will suffer in the end, by their own hand, I’m sure.” And a faint clucking gurgles up from his reedy throat—it’s that most ultimate of ironies, the hard-won last laugh. Because—just when you least expected it—Marilyn Manson has returned, fangs, bared and claws a-slashing with the most grim-humored piledriver of his cage-rattling career. Get used to it, people.

“I had a choice with this record to be punished further,” he smiles coldly, almost surgically, “or to really each everyone a lesson for fucking with me. So Holy Wood is me coming out swinging, and I think it’s something that people are waiting to hear. It’s time to sail the ship again and remind folks who does this the right way.”

Manson’s mountainside digs look like something right of Steven Soderbergh’s film The Lime—artfully long pool leading onto leaf-strewn picturesque patio; tri-level poolhouse wending itself upward via a wrought-iron spiral staircase, from an equipment-jammed lobby (where much of Holy Wood was tracked), to the playback-oriented antechamber (where Manson now sits) , then up to a secluded attic where, he says, he spent many days apart from his girlfriend, apart from the world outside, apart from everything, trying to regain some peace of mind.

Books on the Great Work—alchemy—litter the rooms and the metaphor is telling: à la history’s most misled scientists, Manson, too was seeking a philosopher’s stone--a way to transmute the most lead-ugly experiences to radiant, eye-catching gold. A bottle of France’s most potent absinthe adorns one corner table, replete with requisite grated sugar spoon; during writing/recording, Manson imbibed a great deal of this exotic, potentially dangerous import, he says, so much that the whole process began to teeter on the brink of self-destruction. The liqueur company—in a show of friendship—even sent its illustrious client a branch of the absinthe base element, wormwood.

I’m supposed to soak it in a bottle,” says Manson, scratching his chin with “what if” curiosity. “But I know I’d probably go insane, literally, if I drank it. But wormwood also tied into the album on a couple of weird levels, because it was supposed to be the poison that God sent down to taint the waters to punish mankind. And it’s related to King Solomon, who—as legend has it—had a ring that contained a worm which, when unleashed, could supposedly devour the world. Just like the serpent in [Norse mythology’s Armageddon] Ragnarok, forever eating its own tail.”

Manson stops for a second, his keen eyes blinking behind huge Plexiglas shades. Alchemy. The Illuminati. Biblical prophecy. The Spear Of Destiny. The story of Christ, the fable of Adam and Eve—innocence lost in man’s ruthless quest for knowledge. The more he read, he sighs, “the more the levels just started to pile up. And to even talk about ‘em sounds silly sometimes. But there came a point where it was no longer a situation where you pick up a book and you’re trying to learn from it, trying to understand it—I finally read things that made me realize why I was who I am. I learned that man has a path—whether it’s fate destiny or the cosmic egg, whatever it is—you’ve got something in you and you’re supposed to be that. And some people miss it, they just don’t find it. But I think I found it and I feel like I understand for the first time what my true purpose is.” And that would be? Behind the sunglasses, eyes roll in “like, duh! exasperation. “Why to be Marilyn Manson, of course.”

A creature which—unlike any true chameleon worth its color-changing salt—knows the perfect time and locale to shed its skin. Today, Manson is sporting a simple black ensemble—black jeans, black Velcro-strapped platform boots, the spiderweb tattoos on his mantis-claw forearms peeking out from beneath a skintight long-sleeve black T-shirt. His early years saw him relying on a more Alice Cooper-ish persona, more madcap Munster than malevolent monster. He didn’t haunt that tomb for long; Antichrist Superstar, Manson’s ambitious sophomore work, saw the creation of a Nietzschean will-to-power uberman, free from all moral/societal constraints and—in his neo-Fascist garb—a direct visual descendent of Bob Geldof’s tortured Pink character from the film version of The Wall.

The album’s music—pounding like the machinery in a David Lynch soundtrack—helped push the menacing character across. On ‘98’s Gary Glitter-ish Mechanical Animals, however, Manson changed his stripes again to become The Man Who Fell To Earth-styled starman Omega, creating a squish asexual bodysuit to flesh out the futuristic concept. The Mechanical concerts found him jumping aesthetic trains practically from song to song: Little Hitler one minute, space alien the next, and—while a giant “DRUGS” neon sign flashed behind him for “I Don’t Like The Drugs (But The Drugs Like Me) —an alluring combination of carnival barker and Las Vegas showman. Which—all told—is probably the truest Manson identity of the lot.

But Holy Wood—intended as a prequel to the last two albums/avatars (discounting 1999’s marking-time concert document) —offers us something completely different. In the ornate cover-shot sequence (courtesy of visionary designer Paul Brown), Manson has reconfigured himself as various figures from the tarot deck. In the record and novel—both somewhat autobiographical—he’s reimagined himself as Adam Kadmon, and outsider who so badly wants in on the glamorous high life mass-marketed to him through advertising that he almost sacrifices his very soul to do it. By then, it’s to late—he’s become that which he most despises: a product, and he must incite an über-man revolution (thus foreshadowing Antichrist Superstar) to break free. The set ends with a Quadrophenia -class cliffhanger (underscored by starting sound effects) that’s bound to prod the moral majority out of its Britney Spears slumber.

If you didn’t notice them at first, Marilyn Manson—considerate fellow that he is—will be happy to point them out to you: Crosses, crucifixes, everywhere, hanging on almost all of his retreat walls. Some small, plastic and cheesy, some huge, wooden and intricately carved. Oddly enough, they seem to complement the already-morbid décor of hollow-eyed doll’s heads and Punch and Judy-era handpuppets, carefully preserved under glass. None of Manson’s myriad oil paintings are on display today, however, although he admits to having polished off more than a hundred separate pieces during his recent “blue” period. No, instead it’s Christ that weighs heavily on the afternoon proceedings, Christ that weighs heavily on his mind and Holy Wood scriptures.

The media, even the meddling government, were quick to vilify art, post-Columbine, reckons Manson, art’s most devoted defender. “But there isn’t an image around that’s more grotesque or violent than this, he snaps, pointing to a crucifix dangling directly overhead. “And I don’t think you’re gonna find any writing that’s more offensive than stuff in the Bible.” Cough. Throat-clearing “ahem.” “Uh, not that it offends me. But just to use the status quo of morality, the Bible is very violent. And I started thinking about that during Holy Wood, thinking about films being blamed. And the Zapruder film, which we all saw growing up, constantly on the news, well, there will never be anything more violent or shocking than that. To me, that’s the only thing that’s happened in modern times to equal the crucifixion of Christ. So what I assert on a lot of the record is, ‘Holy Wood’ —which isn’t even that great of a hyberbole of America—is a place where an obituary is just another headline. Where if you die and enough people are watching, then you’re famous.

“And you can see it with all these ‘Real TV’ programs. There’s a new show called Confession, and it’s convicted rapists and murderers telling their stories. And when I heard that, I thought it was like Pope Pius and Andy Warhol’s worst nightmare come true—the ’15 minutes of fame’ think has come to a place where we never imagined it would be. Now, more than ever, everyone wants to be a star, and can be. And more than ever, everyone thinks their opinion is valid—so valid that they have their very own Web site. It’s incredibly narcissistic.”

It’s a whole new tribe, the Cult Of Personality. And Manson—outspoken personality that he is—is nevertheless plotting to bring those false idols down. Musically, he says, “what you’ve seen in my year-long absence is a lot of mediocrity—a lot of rap music and a lot of people thanking God. But I came to acknowledge God in a different way on this record, and not in the way that I had in the past. God definitely exists in what you create, or in the magic that you discover within yourself. And I think Christ was a magician in that sense, and someone that I found I could really relate to, in his being a revolutionary and sacrificing himself for it. Ergo, there’s a strange glimmer of hope in my trilogy. There’s a bitterness and a hatred toward a world that’s too stupid to accomplish certain things, simple forms of evolution. But there’s also hope, because I’m not a a complete pessimist. And that’s a lot of the point of the new record—mankind is predestined to destroy itself. But can we change that? It’s in your hands, kids, whatdaya gonna do to change it?

When Manson tosses around the term “kids,” it’s not as cavalier as it initially appears. He truly believes in today’s youth (as he succinctly proved with that backstage party he threw not so long ago). In a Matrix-mad era—where, Manson firmly believes, “machines are pretty much capable of replacing people, with the only difference being a soul”—teenagers have suddenly sunk to the very bottom-feeding depths of the food chain. “Disposable Teens” (with lines like, “The more that you fear us/The bigger we get/And don’t be surprised when we destroy all of it”) is his take on conundrum.

“I started thinking about the idea that pro-lifers have, where they’re trying to determine when a soul begins to exist. But in Holy Wood, and how I see America now, kids aren’t even considered to have souls until they’re 18, until they’re a valid consumer, until they can vote. They’re just pets, almost. Which is why I see this tension and backlash arising with teenagers—you’re like, ‘Why are these kids acting like this? They have no reason to complain!’ Well, it’s because you’re treating ‘em like they’re dead. So I’m very impressed with the idea that kids have the opportunity now to genuinely cause a revolution if they want to. Because they are in charge—they just don’t know it yet.”

Don’t trust anyone over 30? Uh-oh! Manson—at 31—has now fallen under suspicion. Then again, he seems to relish the role. “I don’t think that I’m a particularly bad person,” he chortles softly. “But I assert myself as a villain to America, because it provides a necessary balance.” Otherwise, he shrugs, it’s an endless cavalcade of knuckleheaded “yo-dude” jock rock.

As Manson concludes his dissertation, he stares idly out of the huge floor-to-ceiling plate-glass window that overlooks his street. As if on cue, an ominous hearse comes creeping down the road like something out of Phantasm. Manson sits bold upright—the deathmobile has jolted him back to reality, to what he describes as “my most important role—as a spiritual leader in a way that Oscar Wilde and Francis Bacon were. They were people who were just making us think, and that’s a spiritual leader. Because someone can’t tell you what your own spirituality is, but they can encourage you to find it. And that’s exactly what I’m trying to do—I’m not trying to help ‘em go get their own answers.”

A perfect lead-in to one final, flickering flashback—back to that dressing room shindig where heart and soul triumphed over goth couture. Exiting from the venue, one awestruck teen was finally able to stammer a message to his plus-one mom: “See? I told you!” he beamed, safely outside in the parking lot. “I told you Manson was cool!” and the mother—equally stunned—slowly began nodding her head in agreement. “you’re right. He was...he was...wonderful!”

Had he overheard it, Manson might’ve shrunk from such a glowing assessment. But it wasn’t altogether unfair. ALT