Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death)

- This article is about the album. For other uses, see In the Shadow of the Valley of Death and Holy Wood (novel).

| Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Studio album by Marilyn Manson | |||||

| Released | November 13, 2000 (United Kingdom) November 14, 2000 (Australia and United States) December 5, 2000 (Japan) |

||||

| Recorded | 1999–2000 Death Valley, California The Mansion Studio (Laurel Canyon, California) |

||||

| Genre | Industrial metal, alternative metal, art rock | ||||

| Length | 68:19 | ||||

| Label | Nothing, Interscope | ||||

| Producer | Marilyn Manson, Dave Sardy | ||||

| Analysis and Interpretations | |||||

|

The Third And Final Beast (Nachtkabarett) |

|||||

| Marilyn Manson chronology | |||||

|

|||||

Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) is the fourth full-length studio album by American rock band Marilyn Manson. It was released on November 13, 2000, in the United Kingdom, on November 14, 2000, in the United States and Australia and on December 5, 2000 in Japan through Nothing and Interscope Records. The album marked a return to the industrial metal style of the band's earlier efforts, after the modernized glam rock sound of Mechanical Animals. As their first release following the Columbine High School massacre on April 20, 1999, Holy Wood served the group as both rebuttal and retort to the accusations leveled against them. The band's frontman described the record as "a declaration of war".[1]

It is a rock opera concept album and the third and final instalment in a trilogy that includes Antichrist Superstar and Mechanical Animals. After its release, Manson revealed that the over-arching story within the trilogy is divulged in reverse chronological order. Holy Wood, therefore, begins the story, followed by Mechanical Animals and concluding with Antichrist Superstar.[2] It was written in Marilyn Manson's former home in the Hollywood Hills and recorded in several "undisclosed" locations, that included Death Valley and Laurel Canyon.

Upon its release, Holy Wood received mixed to positive reviews, with many critics noting that while it was ambitious, it was lacking in execution. Initially, the album was not as commercially successful as the group's two previous outings, taking three years to attain a gold certification from the RIAA. Nevertheless, with worldwide sales of over 9 million copies as of 2011, it has become one of the most successful of their career. It spawned three singles and an abandoned film project that was modified into a novel which currently remains unreleased. The band supported the album with the controversial Guns, God and Government Tour.

On November 10, 2010, British rock magazine Kerrang! published a 10th anniversary commemorative piece in which they called the album "Manson's finest hour [...] A decade on, there has still not been as eloquent and savage a musical attack on the [news] media and mainstream culture [...It is] still scathingly relevant [and] a credit to a man who refused to sit and take it, but instead come out swinging."[1]

Contents

Background and development

- Main article: Rock Is Dead Tour

Template:Quote box

On April 20, 1999, two senior high school students, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, perpetrated the fourth-deadliest school massacre in United States history at their alma mater, Columbine High School.[3] The killers took the lives of 12 students and one teacher, while injuring 21 others, before taking their own lives.[3] In the aftermath, Manson and his eponymous band became a scapegoat.[3][4] Early news media reports alleged that the shooters were fans of the band and had worn the group's concert t-shirts during the massacre.[5][6][7] Growing speculation in the national media and among the public led to their music and imagery, among those of other bands as well as other forms of popular entertainment such as movies and videogames, being blamed for inciting Harris and Klebold to kill their classmates;[1][6][7][8] however, later reports would contradict these allegations and point out that the two not only were not fans of the band but considered them "a joke".[9][10][1][11] In spite of this, the group immediately received widespread criticism from numerous religious, political and entertainment industry figures.[12][13][14][15][16]

A day after the shootings, Michigan State Senator Dale Shugars attended the band's concert at the Van Andel Arena in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Shugars attended to conduct research for a proposed bill which would require parental warnings on concert tickets and promotional material for any performer that had released a record bearing the Parental Advisory sticker in the last five years.[17] He concluded that the band was "part of a drug-cultural type of thing, with a subculture of violence and killing and hatred" and added that "[they] can be part of the blame."[17] On April 25, 1999, conservative pundit William Bennett and Manson archnemesis US Senator Joseph Lieberman[18] claimed the group bore responsibility for the massacre during their appearance on Meet the Press.[6] Three days later, the city of Fresno, California unanimously passed a resolution condemning "Marilyn Manson or any other negative entertainer who encourages anger and hate [...] as an offensive threat to the children of this community."[19] On the same day, the band announced the postponement of the last five North American dates of their then-ongoing Rock Is Dead Tour out of respect for the victims and their grieving families.[20]

The following day, ten US Senators, spearheaded by Sam Brownback of Kansas, signed and sent a letter to Edgar Bronfman Jr., president of Seagrams, which owned Interscope Records, requesting the voluntary cessation of his company's distribution to children of "music that glorifies violence".[21] The letter particularly pointed out the band, among others, for producing songs which "eerily reflect" the actions of Harris and Klebold.[21] The band issued a statement, later in the day, announcing that they had decided to cancel the remaining postponed shows outright.[22][23][24] Two days later, on May 1, 1999, the embattled musician published his Rolling Stone magazine op-ed piece "Columbine: Whose Fault Is It?", as an initial response to the accusations.[25][26][27] In it, he commented,

| “ | I chose not to jump into the [news] media frenzy and defend myself, though I was begged to be on every single TV show in existence. I didn't want to contribute to these fame-seeking journalists and opportunists looking to fill their churches or to get elected [during the US presidential election of 2000] because of their self-righteous finger-pointing. They want to blame entertainment? Isn't religion the first real entertainment? People dress up in costumes, sing songs and dedicate themselves to eternal fandom [...] I'd like [the] media commentators to ask themselves, because their coverage of the event was some of the most gruesome entertainment any of us have seen. | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson Columbine: Whose Fault Is It?[25][26] | ||

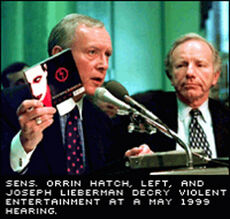

On May 4, 1999, a hearing on the marketing and distribution practices of violent content to minors by the television, music, film and video game industries was conducted before the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.[23] It was chaired by Senator Brownback and comprised of eleven Republicans and nine Democrats, including Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah and Senator Lieberman. The committee heard testimony from cultural observers, professors and mental-health professionals that included Bennett and the Archbishop of Denver, Reverend Charles J. Chaput.[23] Participants criticized the band, its label-mate Nine Inch Nails, and the 1999 Wachowski brothers film The Matrix for their alleged contribution to the environment that made tragedies like Columbine possible.[23] Senators Brownback, Hatch and Lieberman concluded by requesting that the Federal Trade Commission and the United States Department of Justice investigate the entertainment industry's marketing practices to minors.[23][28]

Following the conclusion of the European and Japanese festival leg of the tour on August 8, 1999, the band retreated from public view.[2][1] The album's early development would be marked by the singer's three month seclusion at his then home in the Hollywood Hills.[2] Manson spent this time vacillating on "what I was going to do and how I was going to react".[1] He also admitted that the maelstrom caused him to reconsider whether or not it was judicious to continue to pursue his career since even the entertainment industry had turned against him, stating, "[t]here was a bit of trepidation, [in] deciding, 'Is it worth it? Are people understanding what I'm trying to say? Am I even gonna be allowed to say it?' Because I definitely had every single door shut in my face [...] there were not a lot of people who stood behind me."[2][1][7][12] He would later tell Alternative Press that he also felt a threat to his safety and "a realistic possibility that I could be shot Mark David Chapman-style".[2] After Manson determined that it was less prudent for a controversial artist to allow his detractors to use his work (and entertainment in general) as a scapegoat, he decided to move forward by creating a new album as an extensive counterattack to the accusations.[1][7]

Recording and production

Manson began writing material for the album as early as 1995, prior to the release of Antichrist Superstar in 1996.[29] At the time, the material was scattered in ideas that were "loosely floating around in pieces here and there."[30] During his confinement, he turned his attic into a "writing isolation chamber" where the early material was finally worked into a usable shape.[31][32] Following the conclusion of his three-month hiatus, the band embarked on a year of production, where this material grew into further stages of writing and development.[7][1][33] During this period, each member retained their low profile and Manson stated that their official web site "will be my only contact with humanity."[34]

Template:Quote box The album is the group's most collaborative effort to date, with everyone contributing to the songwriting process, resulting in "the first time that Marilyn Manson sounds like a band."[33][35] Most of the effort was shared by Twiggy Ramirez, John 5 and Marilyn Manson; however, keyboardist Madonna Wayne Gacy also provided input on the songs "President Dead" and "Cruci-Fiction in Space" while Ginger Fish provided all of the drum work.[1][36] Manson said that his songwriting sessions with John 5 took on a very focused approach.[36] He added that there was "rarely an occasion" where their songs and ideas were not completed before being brought to the band for consideration, where they were enthusiastically received.[36] In contrast, his sessions with Twiggy were far less rigorous, as the two experimented freely with absinthe.[36] During the process, the band wrote "a hundred pieces of music and worked maybe 25 or 30 of them into songs."[36] This was subsequently whittled down to the 19 tracks that made it into the final release.[37]

Recording took place in several "undisclosed" locations, including Death Valley and Rick Rubin's The Mansion Studio, in Laurel Canyon.[34][38][35][33] These locations were chosen for the atmosphere they were intended to impart to the music.[33] Mix engineer Dave Sardy was drafted in to co-produce the album with Manson. Bon Harris, of seminal EBM group Nitzer Ebb, was also brought in to supply programming and pre-production editing.[34] A written address was posted by Marilyn Manson on the group's website on December 16, 1999 which announced that the album was now progressing under the working title "In The Shadow Of The Valley Of Death" and represented by the alchemical symbol for Mercury.[34][39][40]

The band's numerous excursions to Death Valley were undertaken to "imprint the feeling of the desert into [the band's] minds", in order to avoid composing songs that sounded "forged" and artificial.[41] Time was also spent recording material, composed mostly of experimental recordings and "acoustic" songs intended for the album and its b-sides.[33] Harris' programming skills proved instrumental since the band would record found and natural sounds which he would manipulate into new sonic elements.[33] Manson later explained that the acoustic songs were only "acoustic" in the sense of "[a] lack of electricity and not a lack of absence."[33] He also clarified that his use of the term "acoustic" to describe the album's sonic landscape was meant to imply that they recorded it using live instrumentation but that it was fundamentally "electronic" in its nature.[33]

The band initially rented recording time at The Mansion due to the suitability of its cavernous rooms for recording drums.[33] Manson explained that it was not something they could accomplish in the limited space of his home studio.[34][33][35][38] However, the band ended up spending a great deal of time at the Laurel Canyon studio because the environment "was very inspiring."[42][43] Ramirez later recalled that these sessions were "all a bit of a blur".[44] He attributed his lack of recollection to "a lot of different emotions racing around [us]" and the rumor that the house, which once belong to escape artist Harry Houdini, was haunted.[44] Gacy shared this opinion but said that he spent the majority of his time working on a computer and synthesizer "mess[ing] around with prime number loops where they only intersect every three days and I'd check up on what kind of music they'd be making. You never know what's going to happen."[42] In contrast, Fish "worked around the clock".[43] The bulk of his contributions to the recording process took place there.[43]

Manson took a short break from the recording sessions on February 23, 2000, to deliver a 20 minute lecture, via satellite, at a current events convention aimed at exposing and dispelling disinformation, titled "DisinfoCon 2000".[45] Six days later, the album was officially titled "Holy Wood (In The Shadow Of The Valley Of Death)".[29] By April 12, 2000, the band had reached the final stages of recording and Manson posted "a silent film documenting our environment for your viewing."[46] He also noted, in pre-release interviews, that the record will be "a very sharp pencil" and sound like "what a fan of Marilyn Manson wants."[35][33][47]

Book and film

- See also Holy Wood (novel) for more details

Manson's ambitions for the project initially included an original screenplay of the same name which would further explore the album's backstory.[1][48] In July 1999 he had reportedly entered negotiations with New Line Cinema to produce and distribute the film and corresponding soundtrack.[29] At the 1999 MTV Europe Music Awards in Dublin, Ireland, on November 11 where the band was to perform,[49] he revealed to "MTV News"' John Norris the title of his then-unrevealed film project and his hopes for it "[to] go into production sometime in the next year."[48] He also met with Chilean avant-garde film maker Alejandro Jodorowsky to discuss the possibility of working on the film although no final decision was made.[49][50] By February 29, 2000, the deal had fallen through due to his reservations that New Line Cinema was taking the film in a direction would not have "retained his artistic vision."[29]

After abandoning his attempt to bring Holy Wood to the big screen, Manson shifted medium for the project and announced plans to put out two books to accompany the then-forthcoming album instead.[29] The first was a "graphic and phantasmagoric" novelized adaptation of the script intended to be released shortly after the record by HarperCollins division ReganBooks.[31] The style of the novel was modeled on and inspired by the authors William S. Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, Aldous Huxley and Philip K. Dick.[33] It was then to be followed by a coffee table book of images created for the "Holy Wood" project.[29]

In an interview with Manson in December 2000, Chuck Palahniuk briefly mentioned the Holy Wood novel and complimented its style. He added it is due for release "next spring".[51] Neither book has yet been released, allegedly due to a publishing dispute.[52] Template:-

Concept

- for a complete overview of the Trilogy see Triptych.

Template:Quote box The album's plot is a "parable"[31] that takes place in a thinly-veiled satire of modern America called "Holy Wood", which Manson has described as "very much like Disney World [...] I thought of how interesting it would be if we created an entire city that was an amusement park, and the thing we were being amused by was violence and sex and everything that people really want to see."[2][53] Its literary foil is "Death Valley", which is used as "a metaphor for the outcast and the imperfect of the world."[54]

The central character is its ill-fated protagonist "Adam Kadmon",[1][29][55] an idealized abstract figure borrowed from the Kabbalah in which he is described as the "Primal Man" or, in the similar Sufic and Alevi philosophy, "Perfect or Complete Man"—the very archetype for humanity.[29] He undertakes a journey, similar to the protagonist in German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra as well as Biblical parables, out of Death Valley and into Holy Wood.[54] Idealistic naïveté entreats him to attempt a subversive revolution through music.[54]

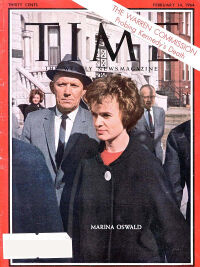

He becomes disenchanted, however, as his revolution is consumed by Holy Wood's ideology of "Guns, God and Government" and co-opted into their culture of death and fame where celebrity-worship, violence and scapegoatism are held as the moral values of a religion rooted in martyrdom.[31][2][1][55][25] In this religion, dead celebrities are venerated into saints and John F. "Jack" Kennedy is idolized as the transfigured Lamb of God and modern-day Christ.[31][54][35][56][57][55][12]

This religion is called "Celebritarianism"[55] and is a deliberate parallel of Christianity to critique both the "Dead Rock Star" martyr and celebrity phenomenon in American celebrity culture and the role that the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ plays as its very blueprint.[56][31][25][2][58][33][12] This concept was extended to the worldwide "Guns, God and Government Tour" that supported the album; the tour's logo was a rifle and handguns arranged to resemble the Christian cross.[59]

Beyond the literal storyline, Manson admitted to Rolling Stone that the storyline is semi-autobiographical and that "[it] can be interpreted on a number of levels, but one of the simplest ways, is about a boy who wants to become part of the world that he doesn't feel adequate for, and the bitterness and rage becomes a revolution inside him, and what happens is that the revolution becomes just another product. When he realizes it's too late, his only choice is to destroy the thing he has created, which is himself."[35][38]

Much like in Mechanical Animals, another lesser character is found in "Coma Black". Similar to the character of "Coma White" from the previous album, Coma Black is an obscure figure which, simultaneously, may or may not be an unattainable ideal, an androgynous facet of Adam or an actual person.[60]

Themes

Template:Quote box Violence is the central subject of the record[61] and it relays this theme by taking a critical look into American society's cultural obsession with firearms, death, and fame, and its ramifications on the Columbine tragedy.[1] In particular it explores what Manson saw as their root causes: gun culture, conservative American Christianity and traditional family values, which it proceeded to dissect to illustrate the more harmful roles they play in the glorification and acceptance of wholesale violence in "mainstream" culture in contrast to music, movies, books or video games.[7][55][62][54] In the album, they are referred to by the slogan "Guns, God and Government".[54][1][11] Seeing similarities between the tumultuous and culturally defining Cold War period of 1960s America and the 1990s, it also draws numerous allegories to that decade and other events and figures in pop culture history.[32][31][12][63][54][53][55][51][61][41] Music journalist Charlotte Robinson pointed out a difficulty in assessing the "narrative's effectiveness" without the book and film and surmised that, "the album doesn't tell much of a story, instead presenting variations on the same themes."[55]

Throughout the album's development Manson was drawn to The Beatles' eponymous 1968 album (colloquially called The White Album) due to its role in the in the Charles Manson 'Family' murders and the parallels that he saw with Columbine.[32][63][12] Finding kinship with the record he noted, "[it] had a lot of very subversive messages on it. Ones they intended and ones that may've [sic] been misinterpreted by [convicted mass murder conspirator] Charles Manson" and that, to his erudition, it was the first piece of music to be blamed and associated with inspiring violence: "When you've got 'Helter Skelter' [taken from a Beatles song of the same name] written in blood on someone's wall, it's a little more damning than anything I've been blamed for."[12][63][32] Regardless, he stated that he "can appreciate it as a powerful record" which became "very inspirational" to the album's conceptualization and that "Holy Wood is a tribute to what that record did in history."[12][63][32][54]

Several music reviewers also noted similarities between the anti-hero character of Adam Kadmon and Charles Manson.[54][12][41] Marilyn Manson echoed this assessment and described Holy Wood as "a declaration of war. In a way, I am declaring war on the United States. Not on everybody, but I am attacking the shallowness of the entertainment industry, their self-congratulatory attitude, their beliefs that they can never do wrong, that they're always right, that they're the center of the universe. It is a clear attack on the entertainment industry."[1] He further articulated that "[i]n one way it's defending Hollywood, and in another way it's attacking it for not being brave enough [by buckling under political pressure]."[41][12]

A substantial amount of the record was also allocated to an analysis of the cultural role of Jesus Christ and the iconography of his crucifixion as the origin of celebrity.[12][33][31][58] In part, the record was an appraisal of "our relationship with Christ, and how we outgrew that".[12] He stated that where in the past he critiqued "everything that was wrong about religion" or fought or simply disregarded it, here he took a different approach by believing the story of Christ on his own terms and "point out things I could relate to".[31][33][64] What he found he could relate to was Christ as a revolutionary figure—a person who was killed for having dangerous opinions that people feared and was, eventually, exploited and "merchandised [by religion] so that they could hang his image on a wall or wear it as a necklace".[31][33] He also remarked that the irony of "religious people who indict entertainment as being violent" was that the crucifixion was the consummate icon of sex and violence that made Jesus "the first rock star" and the exploitation of his stature as "the first celebrity" made religion the root of all entertainment.[58][31][33][64]

Christ's death was then compared to Abraham Zapruder's film of the JFK Assassination during the "Winter of our Discontent,"[32] which Manson observed as, "the only thing that's happened in modern times to equal the crucifixion."[2] Having sarcastically described the historic home video in an op-ed piece for Rolling Stone as "[a] good clip of mankind's generosity to share his violence with the world in such a cinematic way",[65] he took great effort in the album to stress its cultural importance "[a]nd the irony that anyone could complain about violence in films and entertainment when that was shown on the news [...] And that's reality."[31] He explained that having watched it numerous times as a child, it still remained the most violent thing he had ever seen in his life.[31] Juxtaposing the two men together, he posited,

| “ | Christ was the blue-print for celebrity. He was the first celebrity, or rock star if want to look at it that way, and [dying on the cross] he became this image of sexuality and suffering. He’s literally marketed—A crucifix is no different than a concert T-shirt in some ways. I think for America, in my lifetime, John F. Kennedy kind of took the place of that [as a modern-day Christ] in some ways. [After being murdered on TV], he became lifted up as this icon and this Christ figure [by America]. | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson Revelations of an Alien-Messiah[66] | ||

Further exploring the role of Christ and Kennedy, along with John Lennon, as assassination icons, the album made its most critical retort against the band's detractors by casting a spotlight on the universal phenomenon of the news media's veneration of people into media martyrdom by turning their death into spectacle to cater to the American public's hunger for violence, tragedy and celebrity.[1][12][55] He noted, "[y]ou wonder how it would've been had the TV crews been at the crucifixion of Christ"[12] and went on to link these observations to Columbine during an interview on the O'Reilly Factor, when host Bill O'Reilly argued that "disturbed kids" who lacked direction from responsible parents could misinterpret the message of his music to be an endorsement of the sentiment that "when I'm dead everybody's going to know me."

| “ | Well I think that's a very valid point and I think that it's a reflection of, not necessarily this programme but of television in general, that if you die and enough people are watching you become a martyr, you become a hero, you become well known. So when you have these things like Columbine, and you have these kids who are angry and they have something to say and no one's listening, the media sends a message that says if you do something loud enough and it gets our attention then you will be famous for it.

|

” |

| —Marilyn Manson The O'Reilly Factor[69][70] | ||

In spite of the multitude of references to, and thematic fascination, with the three iconic men Manson was reluctant to draw any comparison between them and himself, which he said would have simply amounted to pretentiousness.[61] Instead he volunteered, "[w]hat I did find was parallels in their stories and my story, and I tried to maybe learn from their mistakes and what they tried to do [...] You realise you can't change the world and you can only change yourself, and I think that's what [they] found out."[61] He further added, "[f]or me it was about learning from that and trying to break the evolution of man [since] it's man's nature to be violent."[61]

Composition

Template:Quote box During pre-release interviews Manson stated that Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) was intended to be the "industrial White Album [...] in the sense that it's very experimental. I play a lot of keyboards, we switched things around, wrote in the desert [...] it's experimental and when I think of experimental I think of The White Album."[12] The 1969 Rolling Stones album Let It Bleed became another source of musical and textural inspiration, in part due its connection with the Altamont Free Concert tragedy.[32] Because of this, Manson made a point of noting in interviews that Let It Bleed was written in the same house where he wrote Holy Wood.[32]

Sonically, Manson said the record was "arrogant in an art-rock sense" yet still came out "a lot heavier than anything that anyone would imagine. It's definitely the heaviest record we've ever made. It needs to be to complete the trilogy."[12][33][35] The majority of the songs contain three or four parts, similar to art rock, due to the way that the story is divulged.[33] Despite this the band took great care to avoid being "self-indulgent".[33] Manson contended that "it will please and it will entertain. Art rock is only self indulgent if it bores you. If you make some sort of three-CD compilation instilled with a lot of nonsense that, to me, is self-indulgent."[33] According to CMJ New Music Monthly the songs are "angry and complex".[31] Rolling Stone noted that "on such songs as 'Target Audience (Narcissus Narcosis)', 'Disposable Teens' and 'Cruci-Fiction in Space', [the band] dismantles the slick, glam-tinged sound of [Mechanical] Animals in favor of the more brutal industrial-goth grind of his first album."[38]

Similar to Antichrist Superstar, Holy Wood utilized a compositional device called the song cycle structure which divided the record into the four acts, or movements—A: In the Shadow, D: The Androgyne, A: Of Red Earth and M: The Fallen—to form the framework and outline of Kadmon's story.[63] In keeping with the lyrical style of their two previous records the storyline was unfolded in a multi-tiered progression of drawn out extended metaphors and allusions playing in Manson's psyche.[31] For instance, the album's title was not just a reference to the Hollywood sign but also to "the tree of knowledge that Adam took the first fruit from when he fell out of paradise, the wood that Christ was crucified on, the wood that [Lee Harvey] Oswald's rifle is made from and the wood that so many coffins are made of."[31]

"GodEatGod" followed Adam "contemplating things from Death Valley". "The Love Song" was written as an anthem for Holy Wood's religion of Celebritarianism.[54] The lyrical concept applied dark humor on the idea of "Love Song" (which Manson pointed out was one of the most common titles in music) to satirize America's concept of traditional family values by drawing parallels to the country's love affair with guns and violence: "I was suggesting with the lyrics that the father is the hand, the mother is the gun, and the children are the bullets. Where you shoot them is your responsibility as parents."[62] The chorus was a rhetorical take on an American truck bumper sticker, which asked, "Do you love your God, gun, government?"[54]

UK music magazine Kerrang! described "The Fight Song" as a "playground punk anthem".[47] Manson noted that the theme behind the song was Adam's personal disenchantment and that the track was inherently autobiographical.[54] Speaking broadly, it was about "a person who's grown up all his life thinking that the grass is greener on the other side, but when he finally [gets there], he realises that it's worse than where he came from and that it's truly exploitative."[54] The line, "The death of one is a tragedy, the death of millions is just a statistic", related to the disvaluation of the death of "thousands of other people that die all the time" by the news media when they make "such a big deal when some person dies in such a dramatic way, then for some reason their death [becomes] more relevant."[53]

"Disposable Teens" is a "signature Marilyn Manson song".[54] Its bouncing guitar riff and teutonic staccato had its roots in former glam rocker and convicted pedophile Gary Glitter's song "Rock and Roll, Pt.2".[71] Its lyrical themes tackled the disenfranchisement of contemporary youth, "particularly those that have been [brought up] to feel like accidents", with the revolutionary idealism of their parent's generation.[54][53] The influence of The Beatles was critical in this song.[32].[39][53] The chorus echoed the Liverpool quartet's own disillusionment with the 1960s counterculture movement in the opening lines of their White Album song "Revolution 1".[39][53] Here the sentiment was re-appropriated as a rallying cry for "disposable teens" against the shortcomings of "this so-called generation of revolutionaries", whom the song indicted: "You said you wanted evolution, the ape was a great big hit. You say want a revolution, man, and I say that you're full of shit."[39][53] Manson singled out "Target Audience (Narcissus Narcosis)" as his favorite track from the record and that, to him, it related to every person's desire for self-actualization.[72][54]

Borrowing a riff from English alternative rock band Radiohead ""President Dead"" was a guitar-driven song that showcased John 5's technical skills.[47] The song opened with a vocal sample of Don Gardiner's "ABC News Radio" broadcast of the Death of John F. Kennedy, which is the track's subject matter.[53] On the final mastered sequence, the song is 3:13 in length—a semi-deliberate numerological reference to frame 313 of the Zapruder film, the point where Kennedy's skull exploded from the second round Lee Harvey Oswald fired from his 6.5 x 52 mm Italian Carcano M91/38 bolt-action rifle and the point where JFK assumed his role as an American media martyr "because the production value of his murder was so grand; the cinematography was so well done."[53] "In the Shadow of the Valley of Death" is an introspective song where Adam is at his most emotionally vulnerable and "almost at a point of giving up."[53] "Cruci-Fiction in Space" further delved into the Kennedy assassination and concluded that human beings have simply evolved from being monkeys into man and, finally, into a gun.[31] "A Place in the Dirt" was another personal song characterized by Adam's rumination and self-analysis of his place in Holy Wood.[47]

Template:Quote box "The Nobodies" was a mournful, elegiac dirge that began with a synth-drum and harpsichord intro.[31][47] The verse "[t]oday I'm dirty and I want to be pretty, tomorrow I know I'm just dirt" was sung with an Iggy Pop-style vocal delivery that built into the adrenaline-fuelled chorus of "[w]e are the nobodies, we wanna be somebodies, when we're dead they'll know just who we are. Some children died the other day, we fed machines and then we prayed, puked up and down in morbid faith, you should have seen the ratings that day."[3][31][47] CMJ noted that the song was likely to be interpreted by some people as a tribute to the perpetrators of Columbine but that its point was not to glorify violence, rather, it was to depict a society drenched in its children's blood.[31] "The Death Song" was the turning point for Adam where he no longer cared.[53] Manson described it as having a very sarcastic and nihilistic attitude: "it's like 'We have no future and we don't give a fuck'."[53] Kerrang! described it as among the album's "heaviest" songs.[47]

In "Lamb of God" Manson uses the examples of the assassinations of Jesus Christ, JFK, and John Lennon to criticize his accusers, by illustrating their hunger for venerating dead people into martyrs and superstars and for turning tragedy into a televised spectacle.[1][55] The bridge paraphrased the chorus of "Across the Universe".[32] Manson later noted that even though John Lennon sang that "nothing's going to change my world", "[Lennon's killer] Mark David Chapman came along and proved him very wrong. That was always something, growing up, that was very sad and tragic to me—a song that I always identified with."[32] "Burning Flag" was another heavy metal song that recalled the sound of American industrial metal band Ministry.[47] Lennon's "Working Class Hero" was also covered in the interim between the band's August 30, 2000, appearance at the Kerrang! Awards and the November 14, 2000, launch of the album.[71][32][73] In describing Lennon's idealism and influence on him Manson said that, "some of Lennon's Communist sentiments in his music later in his life were very dangerous. I think he died because of it. I don't think his death was any sort of accident. Aside from that, I think he's one of my favorite songwriters of all time."[71]

Promotion

Promotion for the then-nascent album was largely undertaken through the band's website. After announcing that it will be his only mode of contact with the outside world, Manson regularly employed updates to generate interest and anticipation among fans.[34]

Promotion began as early as June 9, 1999, with an update that he had been busy writing early composition for a new album in tandem with an original screenplay.[74] On December 16, 1999, he posted a four-minute video clip, accompanied by a written address, which elaborated on the upcoming album's themes and featured excerpts of the band performing two new songs inside a studio.[39] The first cut was a rock song that later became the single "Disposable Teens" while the second cut was a rough demo cover of the ballad "Little Child" (otherwise known as "Mommy Dear"), originally sung by Constance Towers in the 1964 Samuel Fuller neo-noir film The Naked Kiss.[39] He also described the nascent album as "the most violent yet beautiful creation we have accomplished. This is a soundtrack for a world that is being sold to kids and then being destroyed by them. But maybe that's exactly what it deserves."[34][39] An acoustic version of the song "Sick City", from Charles Manson's 1970 album Lie: The Love and Terror Cult, later appeared on February 14, 2000, as "an impromptu Valentine's Day gift to fans".[75] The song, however, was not intended to be included in either the upcoming album or the Holy Wood feature film.[76]

On April 12, 2000, Manson wrote from the studio that they were completing the final stages of recording and included a downloadable silent movie that documented the process.[46] This was followed on August 09, 2000, with a posting of the cover of the Holy Wood novel and a soundclip of "The Love Song", the next day.[77] On August 25, 2000, he released three tracks, "Burning Flag", "Cruci-Fiction In Space" and "The Love Song" for digital download on their website.[78] He then traveled to the UK to perform "Disposable Teens" on the October 12, 2000, episode of BBC One's Top of the Pops.[79] Towards the end of the month, on October 27, 2000, the band launched the worldwide Guns, God and Government Tour.[11][80] Video footage and photographs from the inaugural show at the Minneapolis Orpheum Theatre and Milwaukee Eagles Ballroom were posted on the band's website on November 2, 2000, which showed them performing "Disposable Teens" and "The Fight Song".[81]

From November 1 to November 13, 2000, the UK division of Nothing/Interscope Records held a contest to promote both the album and the launch of the UK version of the band's official website. The contest invited fans to log on the site daily to pick up a series of coded clues which led to a message linked to the album. Fans who solved the riddle received an exclusive download and were entered into a draw to win a week-long trip for two to meet the frontman in Hollywood, California.[79] To promote the album in Italy, a promotional CD-ROM called Holy Manson was released in February 2001.

Later, in mid 2001, Universal Music Group received criticism for airing commercials which promoted the album on MTV's Total Request Live (TRL).[82] Manson voiced suspicion that former Democratic vice presidential candidate Senator Joseph Lieberman had a part in its orchestration.[82] At the time the Senator had just introduced a bill to the United States Congress called The Media Marketing Accountability Act, which sought to levy criminal penalties against entertainment industry distributors who market violent and sexually explicit media to minors.[83][84] The proposed legislation stemmed from the publication of the Federal Trade Commission investigation he, along with senators Brownback and Hatch, had requested from then-US President Bill Clinton at the May 4, 1999, Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation hearing on entertainment industry marketing practices to minors.[23][28][85][86][87][88]

Release

Template:Quote box Early in the year, Manson confirmed that the album was on track for a "Fall of 2000" release schedule.[29] By August 2, the singer announced on their website that it was projected for an October 24 release through Nothing/Interscope Records. The announcement was accompanied by an early draft of the tracklisting, listed in no particular order. The following week, weekly previews of the new album featuring new songs or artwork, began appearing on the site in order for fans to be able to "see it and hear it here first before someone gets it inappropriately and without our permission". Manson also stated his desire for the site "to be a place where the true fans can get what they're looking for rather than having to find it through unapproved means."[89] On August 25, 2000, the complete track listing for the new album was released.[78]

On September 18, 2000, Manson clarified, in a nine-minute video posting, that the album's US release was moved to a finalized date of November 14, 2000. He also confirmed that the album's first single was "Disposable Teens".[32][90] It later became apparent that the postponement of the release date came as a result of further fine tuning work during the final mixing stage.[54] In the UK the album was released on November 13, 2000.[91]

On the evening of November 14, 2000, Manson, Ramirez, and John5 took a short break from the tour to celebrate the album's launch by playing a brief invitation-only acoustic set at the Saci nightclub in New York City. Tickets for the event were given away through radio contests, via the band's website or by being among the first 100 to buy the album at the Tower Records store in New York's Broadway Avenue. The set comprised of four songs that included a cover of John Lennon's "Working Class Hero" and Johnny Mandel's theme song for the TV series M*A*S*H, "Suicide Is Painless". Manson noted that the latter song was "[was] far more depressing than anything I could have ever written."[92][93] The following day he appeared on Total Request Live (TRL) in New York's Times Square for a segment titled "Mothers Against Marilyn Manson" ("MAMM").[93] The band later performed the first single at MTV's New Year's Eve celebration, along with a cover of Cheap Trick's "Surrender", and again on January 8, 2001, at the 2001 American Music Awards.[94][95]

Singles

Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) was anchored by three singles. The first two of which were each released in three versions. The first single, "Disposable Teens", debuted as a music video directed by Samuel Bayer[79][96] on Total Request Live (TRL), on October 25, 2000, to help generate future sales for the anticipated album.[79][96] In the following weeks the single was pressed and released into two standalone single EP's. The first version, titled "Disposable Teens Pt.1", was released on November 6, 2000, in the UK[79] and features Manson's cover of "Working Class Hero".[97] The second version, titled "Disposable Teens Pt.2", followed on November 14, 2000, and features a cover of The Doors' "Five to One".[98][99] This version was also released as a 12" picture disc vinyl EP.[100]

The second single, "The Fight Song", was also released was also released in three versions. The first version, titled "The Fight Song Pt.1", was released on January 29, 2001, in the US and on February 19, 2001, in the UK.[101][102][103] "The Fight Song Pt.1" was also released as a 12" picture disc vinyl EP on February 19, 2001, in the UK.[104] Both feature a remix by Joey Jordison of the heavy metal band Slipknot.[105][102] The second version, titled "The Fight Song Pt.2", was released on February 02, 2001, in the US and on March 6, 2001, in the UK.[106][107] The music video was directed by W.I.Z. and generated minor controversy for its violent depiction of a football game between jocks and goths, which some sources interpreted to be directly "echoing" Columbine.[95][102][101] Manson dismissed these claims as "People [wanting to] put into it what [...] helps them sell newspapers or [...] write a headline", adding that "Flak is my job."[102]

As early as February 10, 2001, Manson made indications that the "The Nobodies" would be chosen as the album's third single.[108][109] A music video was directed by Paul Fedor and premiered on MTV in June 2001.[82] Originally, Manson had expressed interest to film the music video in Russia "because the atmosphere, the desolation, the coldness and the architecture would really suit the song."[108] Another initial concept intended to incorporate the MTV stunt and prank TV series, Jackass, due to the song's inclusion in the show's soundtrack.[82] However, this idea was abandoned after the show drew the ire of Senator Joseph Lieberman.[82] The third single was released in physical format, on September 3, 2001, in the UK and, on October 6, 2001, in the US.[110][111][112] A remixed version of the song later appeared in the 2001 Johnny Depp film From Hell.[113]

Cover and packaging

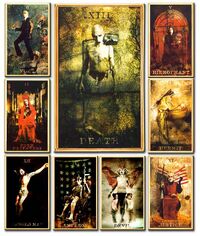

The album artwork was designed by P.R. Brown and Marilyn Manson.[47] Manson began conceptualizing it at the same time that he began writing the record and both Brown and Manson worked in tandem to realize the imagery after they decided that, "rather than bringing in a photographer or an outsider, we'd learn how to do it ourselves."[47] It contains many elements from alchemy and the tarot.[47]

The album uses the symbol of the planet Mercury as an identifying logo, commonly used in alchemy. Expanding on its relationship with the album's concept he stated, "It represents both the androgyne and the prima materia, which has been associated with Adam, the first man. And all of these things are major influences into the writing of the new album."[78]

Manson also commissioned a redesigned set of fourteen Major Arcana tarot cards, based on the Rider-Waite deck.[51] He explained that his interest in them was grounded more on his attraction to their symbolism rather than in the idea of divination.[51] The cards depict each member of the band in a surrealistic tableaux.[51] Each one was reinterpreted to reflect the iconography of the album.[47] For instance: The Emperor is shown with prosthetic legs and clutching a rifle while sitting in a wheelchair in front of an American flag; The Fool is depicted walking off a cliff with grainy images of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and a JFK campaign poster in the background; and Justice weighs The Bible against the Brain.[51] The album's inner sleeve contain nine of these cards: The Magician, The Devil, The Emperor, The Hermit, The Fool, Justice, The High Priestess, Death, and The Hierophant.[47][51] The remaining extant cards include The Star, The World, The Tower, and The Hanged Man.[51]

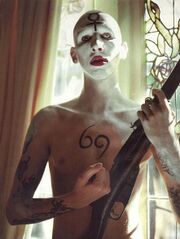

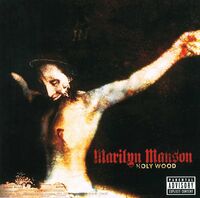

The cover art for Holy Wood portrayed Manson as a crucified Jesus Christ with a torn-off mandible as a criticism on both censorship and America's obsession with media martyrs.[32] It is a cropped version of the reinterpreted Hanged Man card.[47] The Marilyn Manson typeface was taken from the same font used by the Disney World logo in the 1960s.[53] Manson explained his choice for the cover further, "I think it's more offensive to Christians for me to say, 'I believe in the story of Christ and I enjoy the images that you present, but for different reasons than you'. I've taken my own interpretation, that's more offensive than Antichrist Superstar, and just completely disvaluing it. I'm going to turn a bunch of kids onto Christianity in my own sick, twisted way."[53]

The cover generated controversy upon release and had to be offered with a cardboard sleeve featuring an alternative cover due to some retailers refusing to stock the album with the original artwork.[72][114] A pastor in Memphis, Tennessee, also threatened to go on hunger strike unless it was pulled from the shelves.[58] Manson described their actions as attempts at censorship and stated that "the irony is that my point of the photo on the album was to show people that the crucifixion of Christ is, indeed, a violent image. My jaw is missing as a symbol of this very kind of censorship. This doesn't piss me off as much as it pleases me, because those offended by my album cover have successfully proven my point."[114][1] For this reason, Gigwise ranked the cover 16th out of their list of The 50 Most Controversial Album Covers Of All Time!.[115]

Due to the controversy that surrounded the packaging, three different covers for this album exist. The standard cover depicted Manson as The Hanged Man, the censored UK cover depicted "stains" on its cover, and a alternate sleeve release depicted a jawless Manson on the front, and the aforementioned "stains" on the back. Template:-

Formats

Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) was released in three physical formats. The standard jewel case CD release contained a single Enhanced CD, a gatefold booklet and a card stock outer slipcase.[37] The limited UK edition CD featured a bonus track acoustic version of "The Nobodies" while the limited Japanese edition CD contained both the UK bonus track and a live rendition of the song "Mechanical Animals" as bonus material.[116] Universal Music Japan released an Original Recording Remastered version of the album, on December 3, 2008, in Super High Material CD (SHM-CD) and a limited edition 10th anniversary commemorative reissue in 2010.[117][118][119] The LP vinyl release was pressed on two black discs contained in a gatefold paperboard slipcase.[120] The Compact Cassette release contained a single cassette tape, a gatefold booklet and a card stock outer slipcase.[121]

A digital version has been available from Amazon.com in MP3 format since November 14, 2000.[122]

Reception

Critical reception

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 72/100 |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| allmusic | |

| Billboard | (85/100) [124] |

| Entertainment Weekly | (B) [125] |

| LA Weekly | |

| Robert Christgau | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Drowned in Sound | (10/10) [128] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| PopMatters | (favorable)[55] |

| Q | |

Holy Wood received mixed to positive reviews from most music critics.[130] At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the album received an average score of 72, based on 14 reviews, which indicates "generally favorable reviews".[130] Katherine Turman of Amazon, quipped that "[t]he impact of Marilyn Manson's subversive musical agenda has waned, and what's left is a provocative, talented artist writing affecting, powerful, and yes, controversial songs [...] Holy Wood is a musically diverse and powerful statement [...that] is intelligent, dynamic, and multifaceted, with myriad charms that are evident to the tuned-in listener."[131] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of allmusic praised it as "[T]he definitive Marilyn Manson album, since it's tuneful and abrasive." He specifically complimented the band in "figur[ing] out [how] to meld the hooks and subtle sonic shading of Mechanical Animals with the ugly, neo-industrial metallicisms of Antichrist [Superstar]" and said that "much of its charm lies in Manson trying so hard, perfecting details [...] there's so much effort, Holy Wood winds up a stronger and more consistent album than any of his other work. If there's any problem, it's that Manson's shock rock seems a little quaint in 2000 [...However,] it's to Warner's credit as, yes, an artist that Holy Wood works anyway."[123]

Barry Walters of Rolling Stone said that the "The band truly rocks: Its malevolent groove fleshes out its leader's usual complaints with an exhilarating swagger that's the essence of rock and roll."[127] LA Weekly was similarly impressed and pointed out the songs "almost all contain a double-take chord change or a textural overdose or a mind-blowing bridge, and they'll be terroristic in concert."[132] Revolver magazine editor Christopher Scapelliti, on the other hand, was most impressed by the record's earnestness and stated that, "For all Holy Wood's well-tempered melodies and drunken pandemonium, what comes across loudest on the album is not the music but the sense of injury expressed in Manson's lyrics. Like Plastic Ono Band, John Lennon's bare-boned solo debut, Holy Wood screams with a primal fury that's evident even in its quietest moments."[36] According to Billboard magazine, the album proved that Manson was "one of the most skilled lyricists in rock today."[132]

Other critics found larger shortcomings with the album. Drowned in Sound, which assigns a normalized rating out of 10, gave the album a score of 10. They noted, however, "There [are] a number of criticisms that could come Marilyn Manson's way: too much more of the same, too much philosophical posing, too much sloganeering. Regardless, all this needs to attain perfection is a few minutes shaved off of the overall running time [...and] lyrically it actually says something intelligent for once and musically it has a lot more variation and scope than the Limp Bizkits of the world."[128] PopMatters agreed and stated, "The central flaw of Holy Wood is that the power of its message, an important and provocative one, is watered down by its artistic pretensions. While Holy Wood is often affecting, it would be a better album if it was shorter and dealt with its subject matter directly, instead of through the veil of the 'concept album'."[55] Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times was also disappointed that Holy Wood did not live up to "the promise of Mechanical Animals." In steep contrast to Erlewine, he viewed the musical cross-pollination of Antichrist Superstar and Mechanical Animals as confusion on the band's part on "where to turn [musically], as if uncertain which is the right move commercially in a rock world taken over by Limp Bizkit and Eminem." He concluded that "[t]his is music that sounds reasonable on the radio but crumbles under scrutiny."[129] Joshua Klein of The A.V. Club, on the other hand, completely found himself wholly unconvinced and remarked that "[This] sort of agitprop is thoroughly predictable, and the only thing that could prove shocking about Manson's antics would be if the singer actually evinced any power over his followers. Here, he seems entranced by his own power, which may be why his dark worldview sounds baseless even as he offers sharp hooks others would kill for."[133] Template:-

Commercial performance

Since early critical appraisal of Holy Wood was far less favorable than the band's previous effort, Mechanical Animals, many critics and retailers questioned if the band still carried appeal in the music scene of the early 2000's. Best Buy's sales projections in 2000 for the record estimated its first week sales would be around 150,000 units nationally, significantly less than the 223,000 units sold by Mechanical Animals in its first week.[134] In the US, the album debuted and peaked at № 13 on the Billboard 200 with first week sales of 117,000; initially making it a commercial disappointment.[135] Lackluster performance continued to plague the album and, by its second week, it had dropped a massive 47 spots; barely staying inside the Top 60 at the № 60 position.[136] The album's free fall charting trajectory slowed considerably by the following week with a № 76 finish but continued, nevertheless, and by the fourth week it dropped another 25 spots (out of the Top 100 altogether) into № 101.[136] It ended the year with an exit from the Top 130 by charting at № 133.[136]

Segueing into 2001, Holy Wood remained inside the Top 140 after dropping another 7 spots into № 140.[136] However, by the second week, it climbed 47 positions, back inside the Top 100, and settled into № 93 for the week of January 13-20.[136] It didn't stay there for long and, by the following week, landed at № 113.[136] From there the record tumbled 17 spots into № 130 followed by a fall of 13 places into № 143 and another drop of 27 spots to № 170 in the succeeding weeks.[136] It entered its 12th week at № 182 which was followed by a week at № 195, its lowest position, before dropping out of the charts completely on March 3, 2001.[136]

In total, it only spent 13 consecutive weeks on the charts, making it the shortest charting full-length LP offering by the band until 2009's The High End of Low.[136] It was also completely overshadowed by its sister albums, Antichrist Superstar and Mechanical Animals, which spent 52 and 33 weeks on the charts respectively.[136] The album's sales figures were equally dismal and it took the record three years to attain a gold certification from the RIAA, in March 2003, for shipments of over 500,000 units.[137] However, in four other countries, including Australia, Austria, Italy and Sweden, the album peaked in the Top 10.[138] In the UK, the album peaked at № 23.[139] Nevertheless, as of 2011, the album has sold over 9 million copies worldwide, making it one of the most successful in the band's catalogue.[140]

Seventeen months after Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death)'s release, Manson commented on the album's lackluster US sales.[141] He attributed the lack of commercial appeal to the music climate of the time but argued that it stood up comparatively well to contemporary albums in the rock genre.[141] He also noted that the band's US sales figures are usually in the region of one or two million records, "and if I sell less than that I don't think it's such a disaster as if I were to sell seven or eight million records and then go on to sell just half a million records. So there was no disappointment for me."[141]

Accolades

In 2001 Kerrang! named Holy Wood the year's "Best Album" at their annual Kerrang! Awards.[142] During the ceremony, at the Royal Lancaster Hotel in London, Manson sardonically remarked that "[there is] nothing like a good school shooting to inspire a record" as he collected the award.[143]

Kerrang! ranked Holy Wood 9th in their list of Albums of the Year 2000.[144] British magazine NME ranked the album 34th in their critic's picks for the 50 Best Albums of 2000 in their "Decade In Music" series, calling it "A series of heroic rallying cries for the disenfranchised, while also baiting the American Far Right for all its worth."[145] The record ranked 30th in the Critics Top 50[146] and 9th in the Popular Poll[147] of German magazine Musik Express/Sounds in their Albums of the Year 2000. The French edition of the British magazine Rock Sound ranked Holy Wood 15th in the Le choix de la rédaction ("Editor's choice") and 5th in Le choix des lecteurs ("Reader's choice") of their Choix des critiques ("Critic's choice") Albums of the Year 2000.[148] British magazine Record Collector also listed the album among their Best of 2000 list.[149]

Legacy

On their November 10, 2010, issue Kerrang! magazine published a 10th anniversary commemorative piece on the album titled "Screaming For Vengeance"[1] in which they called the album "Manson's finest hour [...] A decade on, there has still not been as eloquent and savage a musical attack on the media and mainstream culture as Manson achieved with Holy Wood [...It is] still scathingly relevant today [...] Compared to his contemporaries, Manson's ideas bristled with intelligence that few could match." The article went on to say, "[...] perhaps that's where Holy Wood achieved its greatest success. In deflecting the attention that was targeted at him back onto the media, they reacted exactly as he knew they would: by blustering and further exposing their own inadequacies [...] The shame of it all, though, is that so little has changed. That the album is still so relevant today suggests it failed in its task of changing attitudes. That it exists at all, though, is a credit to a man who refused to sit and take it, but instead come out swinging."[1]

Guns, God and Government Tour

- Main article: Guns, God and Government

To support the release of Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) the band staged a worldwide stadium tour, 3 days after the album's original release date and 17 days ahead of the album's actual launch, titled the Guns, God and Government Tour.[11][80] Beginning on October 27, 2000, and lasting until September 2, 2001, the tour included six legs spanning Eurasia, Japan and North America with a total of 107 completed shows out of the 109 planned.[11] Typical of the band, the concerts were extremely theatrical[80] with an average show lasting for 1 hour and 40 minutes and the sets designed with communist, religious and "Celebritarian" imagery in mind.[150] Manson had several costume changes throughout the sets: ranging from a Bishop's dalmatic and mitre (often confused for Papal regalia); a costume made from taxidermied animal anatomies (i.e. an epaulette made from a horse's tail, a shirt made from skinned goat heads and ostrich spines); his signature black leather corset; g-string and garter stocking ensemble; an elaborate Roman legionary-style Imperial galea; an Allgemeine SS-style police cap; a black-and-white fur coat; and a giant rising conical skirt that lifted him 12 meters (40 feet) into the air.[80][151][152]

Also common for the band was the constant controversy that followed their tours. The Ozzfest leg was particularly notable on this tour since it marked the band's first performance in Denver, Colorado, (on June 22, 2001, at the Mile High Stadium) following the Columbine High School massacre in nearby Littleton, Colorado. After initially pulling out, due to scheduling conflicts, the band altered their plans in order to accommodate the Denver date.[153] Predictably, the band met heavy resistance from conservative groups and Manson himself received numerous death threats and calls to skip the date.[154][155] A group of church leaders and families, related to Columbine, formed an organization specifically to oppose the show, called 'Citizens for Peace and Respect', which drew the support of Colorado governor Bill Owens and representative Tom Tancredo. On their website, they asserted that the band "promotes hate, violence, death, suicide, drug use, and the attitudes and actions of the Columbine killers".[14] In response, Manson issued a statement, saying,

| “ | I am truly amazed that after all this time, religious groups still need to attack entertainment and use these tragedies as a pitiful excuse for their own self-serving publicity. In response to their protests, I will provide a show where I balance my songs with a wholesome Bible reading. This way, fans will not only hear my so-called, 'violent' point of view, but we can also examine the virtues of wonderful 'Christian' stories of disease, murder, adultery, suicide and child sacrifice. Now that seems like 'entertainment' to me. | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson[14][156] | ||

The Denver show also provided the backdrop for Manson's landmark interview on America's climate of fear and culture of gun violence in Michael Moore's 2002 documentary film Bowling for Columbine. When Moore asked what he would have said if he had the opportunity to speak to the students at Columbine High, he replied, "I wouldn't say a single word. I would listen to what they have to say and that's what no one did."[157]

Two concert films depicting the worldwide tour were recorded. The Guns, God and Government DVD was released on October 29, 2002 by Eagle Rock Entertainment and featured live concert footage spliced from performances in Los Angeles, Europe, Russia and Japan.[158][159] It also included a 30-minute behind-the-scenes featurette titled The Death Parade with guest appearances from Ozzy Osbourne and Eminem.[159] Seven years later it was followed by Guns, God, and Government – Live in L.A. Released on Blu-ray format by Eagle Rock Entertainment division Eagle Records on November 17, 2009; it depicted the sixteen song set of the Los Angeles performance in its entirety.[160][161]

Track listing

All lyrics written by Manson.[37][123]

A: In the Shadow

- 1. "GodEatGod" – 2:34

- 2. "The Love Song" – 3:16

- 3. "The Fight Song" – 2:55

- 4. "Disposable Teens" – 3:01

D: The Androgyne

- 5. "Target Audience (Narcissus Narcosis)" – 4:18

- 6. ""President Dead"" – 3:13

- 7. "In the Shadow of the Valley of Death" – 4:09

- 8. "Cruci-Fiction in Space"' – 4:56

- 9. "A Place in the Dirt" – 3:37

A: Of Red Earth

- 10. "The Nobodies" – 3:35

- 11. "The Death Song" – 3:30

- 12. "Lamb of God" – 4:39

- 13. "Born Again" – 3:20

- 14. "Burning Flag" – 3:21

M: The Fallen

- 15. "Coma Black: a) Eden Eye, b) The Apple of Discord" – 5:58

- 16. "Valentine's Day" – 3:31

- 17. "The Fall of Adam" – 2:34

- 18. "King Kill 33°" – 2:18

- 19. "Count to Six and Die (The Vacuum of Infinite Space Encompassing)" – 3:24

Bonus tracks

- 20. "The Nobodies" (Acoustic Version) (Bonus track on UK and Japanese versions) – 3:33

- 21. "Mechanical Animals" (live) (Bonus track on Japanese version) - 4:41

B-sides

- "Diamonds & Pollen" – 3:55

- "Five to One" (The Doors cover) – 4:22

- "Working Class Hero" (John Lennon cover) – 3:42

- Notes

- The disc contains a data track which leads to a video no longer hosted by Interscope's website.[37] This video was later included as a secret track on the companion DVD of Lest We Forget.[162]

Autopsy

A short film known as Autopsy could be viewed by running a "START.exe" program included in the disk (in the same way one would run a similar program to listen to the hidden track "Untitled" on the previous album Mechanical Animals. While the video, in which a dead Manson has a fetus removed from his skull during autopsy, was originally hosted on the Interscope website it is no longer featured there and can only be viewed as an easter egg on the Lest We Forget (The Best of) bonus DVD.

Album credits

ALL LYRICS BY M. MANSON ·· 1. (music: MANSON) keyboards and bass · synth: Manson · Vocals: Manson · Guitars: John5 · Lead guitar: T. Ramirez · Ambience: M.W. Gacy · Synth: Bon Harris · Noise rhythm guitar: Dave Sardy ·· 2. (music: RAMIREZ., 5) Vocals and outro-lead guitar: Manson · Guitar and Bass: T. Ramirez · Guitars: John5 · Keyboards and samples: M.W. Gacy · Live drums and siren loop: Ginger Fish · Synth and drum programming: Bon Harris ·· 3. (music: 5) Vocals: Manson · Bass and additional guitar: T. Ramirez · Rhythm and lead guitar: John5 · Keyboards and loops: M.W. Gacy · Live drums: Ginger Fish ·· 4. (music: 5, RAMIREZ) Vocals: Manson · Bass: T. Ramirez · Guitar and synth guitar: John5 · Synth and electronic percussion: Bon Harris · Live drums: Ginger Fish · Keyboards: M.W. Gacy · Pills: D. Sardy ·· 5. (music: RAMIREZ, 5) Vocals and Optigan: Manson · Bass and additional lead guitar: T. Ramirez · All guitars: John5 · Loop and live drums: Ginger Fish · Synth and loops: M.W. Gacy · Drum programming and synth: Bon Harris ·· 6. (music: RAMIREZ., 5, GACY) Vocals, syncussion, and mellotron: Manson · Rhythm Guitar and bass: T. Ramirez · Lead and rhythm guitar: John5 · Loop and live drums: Ginger Fish · Keyboards: M.W. Gacy · Backing Vocals: Alex Suttle ·· 7. (music: RAMIREZ., 5) Vocals and distorted flute: Manson · All Keyboards: M.W. Gacy · All guitars: John5 · Death Loop and live drums: Ginger Fish · Bass: T. Ramirez ·· 8. (music: RAMIREZ., 5, GACY) Vocals and piano: Manson · Rhythm guitar, bass: T. Ramirez · Rhythm and lead guitar: John5 · Live drums: Ginger Fish · Keyboards, loops and ambiences: M.W. Gacy · Insect hi-hat: Bon Harris ·· 9. (music: 5) Vocals and Ambience: Manson · Synth bass and keyboards: M.W,. Gacy · Live drums and loop: Ginger Fish · Bass: T. Ramirez · Acoustic, electric and slide guitars: John5 · Synths, sleigh bells and manipulation: Bon Harris ·· 10. (music: 5, MANSON) electric harpsichord: Manson · Guitars: John5 · Bass: T. Ramirez · Keyboards and ambiences: M.W. Gacy · Drum machine and live kit: Ginger Fish · Vocals: Manson ·· 11. (music: 5, MANSON) Vocals: Manson · guitars: John 5 · Bass: T.Ramirez · Synth bass and electronics: Bon Harris · Loop and live drums: Ginger Fish · Children's choir and canned laughter of dead people unsure of why they are laughing: M.W. Gacy ·· 12. (music: RAMIREZ.) Vocals, piano and pianette: Manson · Bass, lead and Leslie guitar, keys and drum loop: T. Ramirez · Acoustic, rhythm and lead guitar: John5 · Live drums: Ginger Fish · Ambience: M.W. Gacy · Synths: Bon Harris ·· 13. (music: RAMIREZ., 5) Vocals and synth bass: Manson · Bass and verse guitar: T. Ramirez · Guitar and lead guitar: John5 · Keyboards: M.W. Gacy · Drum Programming: Ginger Fish and Bon Harris · Bass and other synths: Bon Harris · Additional loops: Danny Saber · Recorded live February 14, 1997 ·· 14. (music: RAMIREZ., 5) Vocals: Manson Guitar and bass: T. Ramirez · Guitar: John5 · Live drums: Ginger Fish · Organic drum programming: Bon Harris and D. Sardy · Synth and destructive manipulation: Bon Harris · Keyboards: M.W. Gacy ·· 15. a)(music: MANSON, 5, RAMIREZ.) Vocals and clean rhythm guitar: Manson · Bass, warped rhythm guitars and add. lead: T. Ramirez · Phase, lead and rhythm guitar: John5 · Loops and live drums: Ginger Fish · Synths, ambience and keyboards: M.W. Gacy · b)(music: MANSON) Vocals and clean guitar: Manson · Rhythm Guitar: John5 · Bass and lead guitar: T. Ramirez · Loop: Ginger Fish ·· 16. (music: RAMIREZ., MANSON) Vocals and piano: Manson · Bass and noise lead guitars: T. Ramirez · Loop and live drums: Ginger Fish · Lead and rhythm guitars: John5 · Keyboards and mellotron: M.W. Gacy · Synthesizers: Bon Harris ·· 17. (music: RAMIREZ., 5) Vocals: Manson · Acoustic, rhythm and synth guitar: John 5 · Bass and rhythm guitar: T. Ramirez · Live drums: Ginger Fish ·· 18. (music: RAMIREZ) Vocals: Manson · Bass: T. Ramirez · Guitars and synth guitars: John5 · Keyboards and Synth: M.W. Gacy · Live drums: Ginger Fish ·· 19. (music: 5) Vocals: Manson · Synth strings and Ambiences: M.W. Gacy · Piano: Bon Harris ····· Celebritarian™ used by permission

···ALL TRACKS ©2000 EMI BLACKWOOD MUSIC ON BEHALF OF ITSELF, SONGS OF GOLGOTHA MUSIC (BMI), BLOOD HEAVY MUSIC (BMI) & DCLXVI MUSIC (BMI). ALL RIGHTS ADMINISTERED WORLDWIDE BY EMI BLACKWOOD MUSIC INC. · MANSON: ALL TRACKS, SONGS OF GOLGOTHA MUSIC · RAMIREZ: ALL TRACKS, BLOOD HEAVY MUSIC, EXCEPT 1, 3, 9, 10, 11, 15b, 19 · JOHN 5: ALL TRACKS, GTR. HACK MUSIC / CHRYSALIS MUSIC ASCAP, EXCEPT 1, 12, 15b, 16, 18 · GACY: TRACKS 6 & 8 DCLXVI MUSIC ©2000 NOTHING/INTERSCOPE RECORDS. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PRINTED IN CANADA.

HOLY WOOD CONCEIVED AND ARRANGED BY MARILYN MANSON

PRODUCED BY MARILYN MANSON & D. SARDY · MIXED BY D. SARDY

ENGINEERED BY GRED FIDELMAN · ALL PRO-TOOLS: GREG FIDELMAN · EDITING, PROGRAMMING & PRE-PRODUCTION BY BON HARRIS · ADDITIONAL ENGINEERING BY PAUL NORTHFIELD · RECORDED @ THE MANSION · ADDITIONAL RECORDING @ HOLLY STUDIOS, SUNSET SOUND FACTORY AND WESTLAKE AUDIO · MIXED @ LARRABEE EAST

ASSISTANT ENGINEERS: NICK RASKULINECZ, JOE ZOOK, KEVIN GUARNIERI AND STEVE MACAULEY · MASTERING: MARCUSSION · MANAGEMMENT: TONY CIULLA/CIULLA MANAGAMENT · BUSINESS MGT: JAY SENDYK · LEGAL: JEFFREY TAYLOR LIGHT · AGENT: RICK ROSKIN, CAA · EU AGENT: EMMA BANKS (HELTER SKELTER) · ART DIRECTION: P.R. BROWN AND MARILYN MANSON · PHOTOGRAPHY & DESIGN: P.R. BROWN @ BAU-DA DESIGN LAB [LA]. · MAKE UP: MARILYN MANSON & RALLIS KAHN

CLOTHING: DEBORAH @ T'AINT · OFFICIAL WEBSITE: MARILYNMANSON.COM

INFO: 7336 SANTA MONICA BLVD., #730, LOS ANGELES, CA 90046

Cover gallery

Charts, certifications and procession

Album

| Charts (2000) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[138] | 8 |

| Austria (Ö3)[138] | 6 |

| Belgium (Flanders) (Ultratop 50)[163][138] | 34 |

| Belgium (Wallonia) (Ultratop)[138] | 29 |

| Canada (CANOE)[136][164] | 13 |

| Germany (Media Control)[165] | 11 |

| Finland (Mitä Hitti)[138] | 25 |

| France (SNEP)[138] | 12 |

| Ireland (IRMA)[166] | 21 |

| Italy (FIMI)[138] | 7 |

| Netherlands (MegaCharts)[138] | 53 |

| Norway (VG-Lista)[138] | 12 |

| New Zealand (RIANZ)[138] | 18 |

| Sweden (Sverigetopplistan)[138] | 7 |

| Switzerland (Hitparade)[138] | 20 |

| United Kingdom (OCC)[167] | 23 |

| United States (Billboard 200)[136][164] | 13 |

| Top Internet Albums[136][164] | 10 |

Certifications

| Region | Provider | Certification | Shipment | Actual Sales |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | CRIA | Gold[168] | 50,000+ | — |

| Switzerland | IFPI | Gold[169] | 20,000+ | — |

| United States | RIAA | Gold[137] | 500,000+ | — |

Singles

Template:Col-begin Template:Col-2

| Single | Chart (2000) | Peak position |

|---|---|---|

| "Disposable Teens" | Australia (ARIA)[170] | 24 |

| France (SNEP)[170] | 67 | |

| Italy (FIMI)[170] | 7 | |

| Netherlands (MegaCharts)[170] | 99 | |

| Sweden (Sverigetopplistan)[170] | 52 | |

| Switzerland (Hitparade)[170] | 73 | |

| United Kingdom (OCC)[167] | 12 | |

| U.S. Billboard Mainstream Rock Tracks[171] | 22 | |

| Billboard Modern Rock Tracks[171] | 24 |

| Single | Chart (2001) | Peak position |

|---|---|---|

| "The Fight Song" | Austria (Ö3)[172] | 59 |

| Finland (Mitä Hitti)[172] | 19 | |

| United Kingdom (OCC)[167] | 24 |

| Single | Chart (2001) | Peak position |

|---|---|---|

| "The Nobodies" | Austria (Ö3)[173] | 56 |

| France (SNEP)[173] | 94 | |

| Italy (FIMI)[173] | 17 | |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[173] | 8 | |

| Switzerland (Hitparade)[173] | 96 | |

| United Kingdom (OCC)[167] | 34 |

Release history

| Region | Date | Label | Format | Catalog |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | November 13, 2000 | Interscope Records | Compact disc | 4908292 |

| Australia | November 14, 2000 | Interscope Records | Compact disc | — |

| North America | November 14, 2000 | Interscope Records | Compact disc | 490790 |

| Japan | December 5, 2000 | Interscope Records | Compact disc | — |

Trivia

- The front cover of the demo Big Black Bus features the band's first use of the term "Holy Wood", where the words "HOLYWOOD PROD." can be seen on the side of the school bus. The term was later used in a July 28, 1999 post by Manson on MarilynManson.net's message board, which opened with the line "Hello from the depths of Holy Wood..."[174]

- The term "Holy Wood" was once used in a poem by Aleister Crowley, to whom Marilyn Manson frequently references. It is also used as a mockery of Hollywood, as per the imagery in the album's cover art.

Personnel

- Marilyn Manson[175]

- Marilyn Manson – arranger, vocals, producer, art direction, concept, syncussion, optigan, mellotron, distorted flute, synth bass, keyboards, piano, pianette, ambiance, electric harpsichord, rhythm guitar

- Twiggy Ramirez – bass, guitar (rhythm, lead, Leslie, warped), keyboards

- John 5 – guitar (lead, rhythm, acoustic, synth, electric, slide, phase)

- Madonna Wayne Gacy – synths, ambiance, keyboards, samples, bass synth, synth strings, mellotron, "Children's choir and canned laughter of dead people unsure of why they are laughing"

- Ginger Fish – drums (live, drum machine), death & siren loops, keyboards

- Production[175]

- Bon Harris of Nitzer Ebb – synthesizers, programming, pre-production editing, organic drum programming, bass, keyboard, "Insect hi-hat", sleigh bells, (destructive) manipulation, electronics, piano

- Paulie Northfield – additional engineering

- D. Sardy (Dave Sardy) – producer, synths, (organic) drum programming, mixing, noise rhythm guitar, "pills"

- P.R. Brown – art direction, design, photography

- Greg Fidelman – engineer, all Pro-Tools

- Nick Raskulinecz – assistant engineer

- Joe Zook – assistant engineer

- Kevin Guarnieri – assistant engineer

- Danny Saber – additional loops

- Alex Suttle – backing vocals

See also

- Marilyn Manson: Mercury Web Address

- Tarot cards

- The Holywood action figures

- References to John F. Kennedy in Marilyn Manson's music

- Guns, God and Government

- Guns, God and Government World Tour (DVD)

- Guns, God, and Government World Tour book

- The Death Parade

- Holy Manson

References

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Jones, Steve (August 2002). Pop music and the press. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 1-56639-966-1.

| Marilyn Manson discography | |

|---|---|

| Studio albums | Portrait of an American Family • Antichrist Superstar • Mechanical Animals • Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) • The Golden Age of Grotesque • Eat Me, Drink Me • The High End of Low • Born Villain • The Pale Emperor • Heaven Upside Down • WE ARE CHAOS • Twelfth studio album |

| EPs | Smells Like Children • Remix & Repent • The Nobodies: 2005 Against All Gods Mix • Hot Topic download card • Slo-Mo-Tion Remix EP |

| Demos | The Raw Boned Psalms • The Beaver Meat Cleaver Beat • Big Black Bus • Grist-o-Line • Lunchbox • After School Special • Thrift • Live as Hell • The Family Jams • Refrigerator • The Manson Family Album |

| Compilations | The Last Tour on Earth • Lunch Boxes & Choklit Cows • Lest We Forget – The Best Of • iTunes Essentials: Marilyn Manson • Second remasters compilation • Lost & Found |

Cite error: <ref> tags exist, but no <references/> tag was found

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "N", but no corresponding <references group="N"/> tag was found, or a closing </ref> is missing