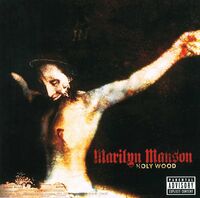

Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death)

| Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||

| Studio album by Marilyn Manson | |||||

| Released | November 13, 2000 (United Kingdom) November 14, 2000 (Australia and United States) December 5, 2000 (Japan) |

||||

| Recorded | 1999–2000 Death Valley, California The Mansion Studio (Laurel Canyon, California) |

||||

| Genre | Alternative Metal, Industrial Metal[1], Hard Rock [2], Art Rock, Gothic rock [3] | ||||

| Length | 68:19 | ||||

| Label | Nothing, Interscope | ||||

| Producer | Marilyn Manson, Dave Sardy | ||||

| Discogs | |||||

| Analysis and Interpretations | |||||

|

The Third And Final Beast (Nachtkabarett) |

|||||

| Marilyn Manson chronology | |||||

|

|||||

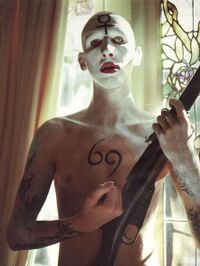

Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) is the fourth full-length studio album by American rock band Marilyn Manson, released in November 2000 through Nothing and Interscope Records. The album marked a return to the industrial metal style of the band's earlier efforts, after the modernized glam rock sound of Mechanical Animals. As their first release following the Columbine High School massacre of April 20, 1999, Holy Wood served as Marilyn Manson's rebuttal to the accusations leveled against them in the wake of that incident. The band's frontman, Marilyn Manson, described the record as "a declaration of war".[4]

A rock opera concept album, it is the third and final instalment in a trilogy that includes Antichrist Superstar and Mechanical Animals. After its release, Manson divulged that the over-arching story within the trilogy is presented in reverse chronological order; Holy Wood, therefore, begins the story, followed by Mechanical Animals and concluding with Antichrist Superstar.[5] It was written in Marilyn Manson's former home in the Hollywood Hills and recorded in several "undisclosed" locations, including Death Valley and Laurel Canyon.

Upon its release, Holy Wood received mixed to positive reviews, with many critics noting that while it was ambitious, it was lacking in execution. Initially, the album was not as commercially successful as the group's two previous outings, taking three years to attain a gold certification from the RIAA. Nevertheless, with worldwide sales of over 9 million copies as of 2011, it has become one of the most successful of their career. It spawned three singles and an abandoned film project that was modified into the as-yet unreleased Holy Wood novel. Marilyn Manson supported the album with the controversial Guns, God and Government Tour.

On November 10, 2010, British rock magazine Kerrang! published a 10th-anniversary commemorative piece in which they called the album "Manson's finest hour ... A decade on, there has still not been as eloquent and savage a musical attack on the [news] media and mainstream culture ... [It is] still scathingly relevant [and] a credit to a man who refused to sit and take it, but instead come out swinging."[4]

Contents

Background and development

- Main article: Rock Is Dead (tour)

| “ | "Ninety-nine was a pivotal year — as was 1969, the year of my birth. The two years share many similarities. Woodstock '99 [where rape and mass looting were rife], became an Altamont [the Rolling Stones concert in 1969 where the Hell's Angels beat a fan to the death] of its own. Columbine became the Manson murders of our generation. Things happened that could've made me want to stop making music. Instead, I decided to come out and really punish everyone for daring to fuck with me. I've got a big fight ahead of me on this one. And I want every bit of it." | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson[6] | ||

During the 1990s Marilyn Manson and his eponymous band established themselves as one of the most controversial rock acts in music history.[7] The band became a household name with the mainstream success of their albums Antichrist Superstar (1996) and Mechanical Animals (1998).[7] By the time of their Rock Is Dead Tour in 1999, the band's outspoken frontman had become a culture war iconoclast and a rallying icon for alienated youth.[7]

As their popularity rose, the transgressive and confrontational nature of their music and imagery angered social conservatives.[8] Politicians from both sides of the political spectrum lobbied to have their performances banned, citing rumors that the shows contained animal sacrifices, bestiality, and rape.[7] Their concerts were picketed by religious advocates and parent groups, who asserted that their music had a corrupting influence on youth culture by inciting "rape, murder, blasphemy and suicide".[8]

On April 20, 1999, Columbine High School students Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold took the lives of 12 students and one teacher, while injuring 21 others, before taking their own lives.[9] In the aftermath of the fourth-deadliest school massacre in United States history, the band became a "scapegoat".[9][10] Early news media reports alleged that the shooters were fans of the band, and had worn the group's concert t-shirts during the massacre.[11][12] Speculation in the national media and among the public led to Manson's music and imagery being blamed for inciting Harris and Klebold.[4][13] However, later reports pointed out that the two were not fans of the band, and considered them "a joke".[14][15] In spite of this, the group—alongside other bands and forms of popular entertainment such as movies and video games—received widespread criticism from religious, political, and entertainment industry figures.[6][16][17]

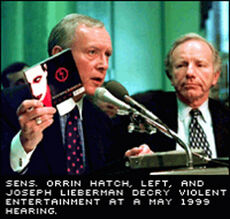

A day after the shootings, Michigan State Senator Dale Shugars attended the band's concert at the Van Andel Arena in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to conduct research for a proposed bill which would require parental warnings on concert tickets and promotional material for any performer that had released a record bearing the Parental Advisory sticker in the last five years.[18] He concluded that the band was "part of a drug-cultural type of thing, with a subculture of violence and killing and hatred" and added that "[they] can be part of the blame".[18] During their appearance on Meet the Press on April 25, 1999, conservative pundit William Bennett and longtime Manson archnemesis US Senator Joseph Lieberman[8] claimed the group bore responsibility for the massacre during their appearance on Meet the Press.[12] Three days later, the city of Fresno, California unanimously passed a resolution condemning "Marilyn Manson or any other negative entertainer who encourages anger and hate ... as an offensive threat to the children of this community."[19] On the same day, the band announced the postponement of the last five North American dates of their tour out of respect for the victims and their grieving families.[20]

The following day ten US Senators, spearheaded by Sam Brownback of Kansas, signed and sent a letter to Edgar Bronfman Jr.—president of Seagrams, which owned Interscope Records—requesting the voluntary cessation of his company's distribution to children of "music that glorifies violence."[21][22] The letter cited Marilyn Manson, among other bands, as producing songs which "eerily reflect" the actions of Harris and Klebold.[21][22] Later in the day, the band announced the outright cancellation of the remaining shows.[23] On May 1, 1999, Manson published a Rolling Stone magazine op-ed piece titled "Columbine: Whose Fault Is It?" as an initial response to the accusations.[24][25] In it, he commented,

| “ | I chose not to jump into the [news] media frenzy and defend myself, though I was begged to be on every single TV show in existence. I didn't want to contribute to these fame-seeking journalists and opportunists looking to fill their churches or to get elected [during the US presidential election of 2000] because of their self-righteous finger-pointing. They want to blame entertainment? Isn't religion the first real entertainment? People dress up in costumes, sing songs and dedicate themselves to eternal fandom ... I'd like [the] media commentators to ask themselves, because their coverage of the event was some of the most gruesome entertainment any of us have seen. | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson Columbine: Whose Fault Is It?[26] | ||

On May 4, 1999, a hearing on the marketing and distribution practices of violent content to minors by the television, music, film, and video game industries was conducted before the United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation.[27] The committee heard testimony from cultural observers, professors and mental-health professionals that included William Bennett and the Archbishop of Denver, Reverend Charles J. Chaput.[27] Participants criticized the band, its label-mate Nine Inch Nails, and the 1999 Wachowski brothers film The Matrix for their alleged contribution to the environment that made tragedies like Columbine possible.[27] The committee requested that the Federal Trade Commission and the United States Department of Justice investigate the entertainment industry's marketing practices to minors.[27][28]

Following the conclusion of the European and Japanese festival leg of the tour on August 8, 1999, the band retreated from public view.[4][5] The album's early development was marked by Manson's three-month seclusion at his home in the Hollywood Hills.[5] The singer spent this time vacillating on "what I was going to do and how I was going to react".[4] He admitted that the maelstrom caused him to reconsider whether to continue pursuing his career: "[t]here was a bit of trepidation, [in] deciding, 'Is it worth it? Are people understanding what I'm trying to say? Am I even gonna be allowed to say it?' Because I definitely had every single door shut in my face ... there were not a lot of people who stood behind me."[5][6] He told Alternative Press that he felt his safety was threatened, to the point where he "could be shot Mark David Chapman-style".[5] Manson concluded that it was less prudent for a controversial artist to allow his detractors to use his work (and entertainment in general) as a scapegoat, and began work on the new album to level a more extensive counterattack.[4][29]

Recording and production

Manson began writing material for the album as early as 1995, prior to the release of Antichrist Superstar.[30] Initially the material consisted of loosely scattered ideas "floating around in pieces here and there".[31] Manson isolated himself in his attic, where the early material was worked into a usable shape.[32][33] At the conclusion of Manson's three-month hiatus the band embarked on a year of writing and development of the material.[29][4][34] Band members maintained a low profile; Manson stated that their official web site would "be my only contact with humanity."[35]

| “ | "I'm at that point in my career where I wanted to make this film and I'm making this new record, where I really examine suffering and where celebrities come from. How it all kind of traces back in religion, and celebrities and Hollywood all kind of relate to each other. And that's very American." | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson[36] | ||

The album is the group's most collaborative effort to date, with everyone contributing to the songwriting process, resulting in a more unified sound.[34][37] Most of the effort was shared by Twiggy Ramirez, John 5, and Marilyn Manson; keyboardist Madonna Wayne Gacy provided input on the songs ""President Dead"" and "Cruci-Fiction in Space", while Ginger Fish provided all of the drum work.[4][38] Manson said that his songwriting sessions with John 5 were very focused;[38] most of the songs were complete before being brought to the band for consideration, where they were enthusiastically received.[38] In contrast, his sessions with Ramirez were far less rigorous, as the two experimented with absinthe.[38] During the process the band wrote a hundred pieces, of which 25 or 30 were developed into songs.[38] Of these, 19 tracks were selected for the album.[39]

Recording took place in several "undisclosed" locations, including Death Valley and Rick Rubin's The Mansion Studio in Laurel Canyon.[34][35][37][40] Locations were chosen for the atmosphere they were intended to impart to the music.[34] Mix engineer Dave Sardy co-produced the album with Manson. Bon Harris, of seminal Electronic body music group Nitzer Ebb, supplied programming and pre-production editing.[35] Manson announced on December 16, 1999, that the album was progressing under the working title "In the Shadow of the Valley of Death" and would be represented by the alchemical symbol for Mercury.[35][41][42]

The band's numerous excursions to Death Valley were undertaken to "imprint the feeling of the desert into [the band's] minds", in order to avoid composing songs that sounded "forged" and artificial.[43] Experimental recordings and "acoustic" songs were recorded using live instrumentation. Manson later explained that the acoustic songs were only "acoustic" in the sense of not being produced electrically; the album's sonic landscape is fundamentally "electronic". Harris' programming skills proved instrumental, as the band recorded found and natural sounds, which he manipulated into new sonic elements.[34]

The band rented recording time at The Mansion Studio, as its cavernous rooms are suitable for recording drums.[34] The band found the space inspiring, and spent a lot of time there;[44][45] they found they could accomplish more there than in the limited space of Manson's home studio.[34][35][37][40] Ramirez later had blurry recollections of the sessions;[46] he found there were "a lot of different emotions racing around [us]". The house, which once belong to escape artist Harry Houdini, is rumored to be haunted.[46] Gacy shared this opinion, but said that he spent the majority of his time working on a computer and synthesizer, "mess[ing] around with prime number loops where they only intersect every three days and I'd check up on what kind of music they'd be making. You never know what's going to happen."[44] In contrast, Fish worked constantly; the bulk of his contributions to the recording process took place at The Mansion.[45]

On February 23, 2000, Manson delivered a 20-minute lecture, via satellite, at a current events convention titled "DisinfoCon 2000", aimed at exposing and dispelling disinformation.[47] Six days later the album was officially titled Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death).[30] By April 12, 2000, the band had reached the final stages of recording, and Manson posted footage of the recording studio.[48] In pre-release interviews he noted that the record would be "a very sharp pencil" that would appeal to Marilyn Manson fans.[49]

Book and film

- See also Holy Wood (novel) for more details

Manson's ambitions for the project initially included a film of the same name which would explore the album's backstory.[4][36] In July 1999 he had reportedly entered negotiations with New Line Cinema to produce and distribute the film and its soundtrack.[30] At the 1999 MTV Europe Music Awards in Dublin, Ireland, where the band was to perform on November 11,[50] he revealed film's title and his projected production plans.[36] He also met with Chilean avant-garde film maker Alejandro Jodorowsky at the event to discuss the possibility of working on the film, although no final decision was made.[50][51] By February 29, 2000, the deal had fallen through due to Manson's reservations that New Line Cinema was taking the film in a direction that would not have "retained his artistic vision."[30]

Abandoning his attempt to bring Holy Wood to the big screen, Manson instead announced plans to put out two books to accompany the album.[30] The first was a "graphic and phantasmagoric" novelized adaptation, intended to be released shortly after the record by ReganBooks, a division of HarperCollins.[32] The style of the novel was inspired by the authors William S. Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut, Aldous Huxley, and Philip K. Dick.[34] It was to be followed by a coffee table book of images created for the project.[30]

In an interview with Manson in December 2000 novelist Chuck Palahniuk briefly mentioned the Holy Wood novel, and complimented its style. The book was due for release in the spring of 2001.[52] Neither book has yet been released, allegedly due to a publishing dispute.[53]

Concept

- for a complete overview of the Trilogy see Triptych.

| “ | "'Holy Wood'—which isn't even that great of a hyperbole of America—is a place where an obituary is just another headline. Where if you die and enough people are watching, then you're famous." | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson on the album's concept.[5] | ||

The album's plot is a "parable"[32] that takes place in a thinly-veiled satire of modern America called "Holy Wood", which Manson has described as "very much like Disney World ... I thought of how interesting it would be if we created an entire city that was an amusement park, and the thing we were being amused by was violence and sex and everything that people really want to see."[5][54] Its literary foil is "Death Valley", which is used as "a metaphor for the outcast and the imperfect of the world."[55]

The central character is its ill-fated protagonist "Adam Kadmon",[4][30][56] a figure borrowed from the Kabbalah, in which he is described as the "Primal Man". In the similar Sufic and Alevi philosophies, he is described as the "Perfect or Complete Man"—an archetype for humanity.[30] He undertakes a journey, similar to the protagonist in German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Biblical parables, out of Death Valley and into Holy Wood.[55] Idealistic naïveté entreats him to attempt a subversive revolution through music.[55]

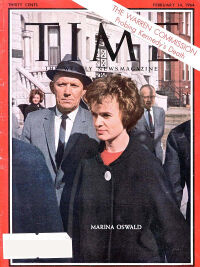

While disenchanted when his revolution is consumed by Holy Wood's ideology of "Guns, God and Government", he is co-opted into their culture of death and fame, where celebrity-worship, violence, and scapegoatism are held as the moral values of a religion rooted in martyrdom.[4][5][24][32][56] In this religion dead celebrities are venerated into saints and President John F. "Jack" Kennedy is idolized as the transfigured Lamb of God and modern-day Christ.[32][55][37][57][58][56][6]

This religion, called "Celebritarianism",[56] is a deliberate parallel of Christianity. The intention is to critique the dead-celebrity phenomenon in American culture and the role that the Crucifixion of Jesus plays as its blueprint.[5][6][24][32][34][57][59] This concept was extended to the worldwide Guns, God and Government Tour that supported the album; the tour's logo was a rifle and handguns arranged to resemble the Christian cross.[60]

Manson told Rolling Stone that the storyline is semi-autobiographical. While it can be viewed on several levels, Manson states the simplest interpretation is to see it as a story about an angry youth whose revolution becomes commercialized, which leads him to "destroy the thing he has created, which is himself."[37][40]

Much like in Mechanical Animals, another lesser character is found in "Coma Black". Similar to the character of "Coma White" from the previous album, Coma Black is an obscure figure which, simultaneously, may or may not be an unattainable ideal, an androgynous facet of Adam or an actual person.[61]

Themes

| “ | "[Holy Wood is] not necessarily [all] about the Columbine incident, but more the reason why it happened ... [It's about] the way America raises its kids to feel like they're unwanted and made to feel like they're dead already. They really don't have anything to live for and it's also concerned with the repercussions of that incident." | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson on the album's thematic preoccupation.[4] | ||

Violence is the central subject of the record.[62] The material explores this theme by taking a critical look at America's cultural obsession with firearms, death, and fame, and its ramifications with respect to the Columbine tragedy.[4] Manson sees the root causes of Columbine as gun culture, conservative American Christianity, and traditional family values. The album illustrates the harmful roles they play in the glorification and acceptance of wholesale violence in "mainstream" culture.[29][56][63][55] In the album these factors are referred to by the slogan "Guns, God and Government."[55][4][64] Seeing similarities between the tumultuous and culturally defining Cold War period of 1960s America and the 1990s, Manson draws numerous allegories to that decade and other events and figures in pop culture history.[33][32][6][65][55][54][56][52][62][43] Music journalist Charlotte Robinson pointed out that it is difficult to assess the "narrative's effectiveness" without the book and film, and stated that "the album doesn't tell much of a story, instead presenting variations on the same themes."[56]

Manson was drawn to The Beatles's White Album due to its purported role in the Charles Manson 'Family' murders and parallels he saw between that incident and Columbine.[33][65][6] Finding kinship with the record he noted, "[it] had a lot of very subversive messages on it. Ones they intended and ones that may've [sic] been misinterpreted by [convicted mass murder conspirator] Charles Manson" and that, to his erudition, it was the first piece of music to be blamed and associated with inspiring violence: "When you've got 'Helter Skelter' [taken from a Beatles song of the same name] written in blood on someone's wall, it's a little more damning than anything I've been blamed for."[6][65][33] He stated that he "can appreciate it as a powerful record" which was "very inspirational" to his album's concept. Holy Wood, he said, "is a tribute to what that record did in history."[6][65][33][55]

Several music reviewers also noted similarities between the anti-hero character of Adam Kadmon and Charles Manson.[6][43][55] Marilyn Manson echoed this assessment, and described Holy Wood as "a declaration of war. In a way, I am declaring war on the United States. Not on everybody, but I am attacking the shallowness of the entertainment industry, their self-congratulatory attitude, their beliefs that they can never do wrong, that they're always right, that they're the center of the universe. It is a clear attack on the entertainment industry."[4] He further articulated that "[i]n one way it's defending Hollywood, and in another way it's attacking it for not being brave enough."[6][43]

A substantial amount of the record analyzes the cultural role of Jesus Christ and the iconography of his crucifixion as the origin of celebrity.[6][32][34][59] The album appraises "our relationship with Christ, and how we outgrew that."[6] He states that where in the past he critiqued religion, with this album accepts the story, and looks for things he could relate to.[32][34] He discovered Christ was a revolutionary figure—a person who was killed for having dangerous opinions, and was later exploited and merchandised by religion.[32][34]= Manson notes the irony of "religious people who indict entertainment as being violent", because the crucifixion is a consummate icon of sex and violence which made Jesus "the first rock star". He feels that the exploitation of Christ as "the first celebrity" made religion the root of all entertainment.[32][34][59]

Christ's death is compared to Abraham Zapruder's film of the JFK Assassination during the "Winter of our Discontent,"[33] which Manson observed as, "the only thing that's happened in modern times to equal the crucifixion."[5] He sarcastically described the historic home movie in an op-ed piece for Rolling Stone as "[a] good clip of mankind's generosity to share his violence with the world in such a cinematic way".[66] Manson stresses the film's cultural importance and notes the irony of showing such violence on the news while complaining about violence in the entertainment industry.[32] He watched the clip numerous times as a child, and finds it the most violent thing he had ever seen.[32] Juxtaposing Christ and Kennedy, he posited,

| “ | Christ was the blue-print for celebrity. He was the first celebrity, or rock star if want to look at it that way, and [dying on the cross] he became this image of sexuality and suffering. He’s literally marketed—A crucifix is no different than a concert T-shirt in some ways. I think for America, in my lifetime, John F. Kennedy kind of took the place of that [as a modern-day Christ] in some ways. [After being murdered on TV], he became lifted up as this icon and this Christ figure [by America]. | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson Revelations of an Alien-Messiah[67] | ||

Manson also cites John Lennon as an assassination icon, and uses the album to criticize the news media's veneration of people into media martyrdom, and the tendency to turn death into spectacle to cater to the American public's appetite for violence, tragedy, and celebrity. He uses this to rebut claims that Marilyn Manson's music was responsible for Columbine.[4][6][56] He wonders how the media would have covered the crucifixion,[6] and linked these observations to Columbine during an interview on the O'Reilly Factor. Bill O'Reilly argued that "disturbed kids" who lack direction from responsible parents could misinterpret the message of his music to be, in fact, an endorsement of the mentality that "when I'm dead [then] everybody's going to know me." Manson responded:

| “ | Well I think that's a very valid point and I think that it's a reflection of, not necessarily this programme but of television in general, that if you die and enough people are watching you become a martyr, you become a hero, you become well known. So when you have these things like Columbine, and you have these kids who are angry and they have something to say and no one's listening, the media sends a message that says if you do something loud enough and it gets our attention then you will be famous for it.

|

” |

| —Marilyn Manson The O'Reilly Factor[70][71] | ||

In spite of the many references to, and thematic fascination with, the three iconic men, Manson was reluctant to draw any comparison between them and himself, which he said would have amounted to pretentiousness.[62] Instead he volunteered, "[w]hat I did find was parallels in their stories and my story, and I tried to maybe learn from their mistakes and what they tried to do ... You realise you can't change the world and you can only change yourself, and I think that's what [they] found out."[62] He further added, "[f]or me it was about learning from that and trying to break the evolution of man [since] it's man's nature to be violent."[62]

Composition

| “ | "Is adult entertainment killing our children? Or is killing our children entertaining adults?" | ” |

| —Introductory statement on the band's website during the Holy Wood era.[41] | ||

During pre-release interviews Manson stated that Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death) was intended to be the "industrial White Album ... in the sense that it's very experimental. I play a lot of keyboards, we switched things around, wrote in the desert ... it's experimental and when I think of experimental I think of The White Album."[6] The 1969 Rolling Stones album Let It Bleed became another source of musical and textural inspiration and Manson made a point of noting in interviews that it was written in the same house where he wrote Holy Wood.[33]

Sonically, Manson said the record was "arrogant in an art rock sense", yet it turned out to be the "heaviest" record the band has done. "It needs to be to complete the trilogy," he said.[6][34][37] The majority of the songs contain three or four parts, similar to art rock, due to the way that the story is told.[34] The band took great care to avoid being "self-indulgent".[34] Manson contended that "it will please and it will entertain. Art rock is only self indulgent if it bores you. If you make some sort of three-CD compilation instilled with a lot of nonsense that, to me, is self-indulgent."[34] According to CMJ New Music Monthly, the songs are "angry and complex".[32] Rolling Stone noted that "on such songs as 'Target Audience (Narcissus Narcosis)', 'Disposable Teens' and 'Cruci-Fiction in Space', [the band] dismantles the slick, glam-tinged sound of [Mechanical] Animals in favor of the more brutal industrial-goth grind of his first album."[40]

Similar to Antichrist Superstar, Holy Wood utilizes a compositional device called the song cycle structure, which divides the record into four movements—A: In the Shadow, D: The Androgyne, A: Of Red Earth and M: The Fallen—to form the framework of Kadmon's story.[65] In keeping with the lyrical style of their two previous records the storyline unfolds in a multi-tiered progression of drawn out extended metaphors and allusions playing in Manson's psyche.[32] For instance, the album's title was not just a reference to the Hollywood sign but also to "the tree of knowledge that Adam took the first fruit from when he fell out of paradise, the wood that Christ was crucified on, the wood that [Lee Harvey] Oswald's rifle is made from and the wood that so many coffins are made of."[32]

"GodEatGod" follows Adam as he contemplates in the desert.[55] "The Love Song" was written as an anthem for Holy Wood's religion of Celebritarianism.[55] The lyrical concept applies dark humor on the idea of "Love Song" (which Manson pointed out was one of the most common titles in music) to satirize America's concept of traditional family values by drawing parallels to the country's love affair with guns and violence: "I was suggesting with the lyrics that the father is the hand, the mother is the gun, and the children are the bullets. Where you shoot them is your responsibility as parents."[63] The chorus is a rhetorical take on an American bumper sticker, which asks: "Do you love your God, gun, government?"[55]

UK music magazine Kerrang! described "The Fight Song" as a "playground punk anthem".[49] Manson noted that the song's theme is Adam's desire to be a part of Holy Wood; the track is inherently autobiographical.[55] Speaking broadly, it is about "a person who's grown up all his life thinking that the grass is greener on the other side, but when he finally [gets there], he realises that it's worse than where he came from and that it's truly exploitative."[55] The line, "The death of one is a tragedy, the death of millions is just a statistic", relates to the disvaluation of the deaths of ordinary people who die every day, who are ignored by the media, compared to the frenzy that results in the press when someone dies in a more dramatic way.[54]

"Disposable Teens" is a "signature Marilyn Manson song".[55] Its bouncing guitar riff and teutonic staccato has its roots in former glam rocker and convicted pedophile Gary Glitter's song "Rock and Roll, Pt.2".[72] Its lyrical themes tackle the disenfranchisement of contemporary youth, "particularly those that have been [brought up] to feel like accidents", with the revolutionary idealism of their parent's generation.[55][54] The influence of The Beatles was critical in this song;[33][41][54] the chorus echoes the disillusionment expressed in opening lines of their White Album song "Revolution 1".[41][54] Here the sentiment was appropriated as a rallying cry for "disposable teens" against the shortcomings of "this so-called generation of revolutionaries", whom the song indicted: "You said you wanted evolution, the ape was a great big hit. You say want a revolution, man, and I say that you're full of shit."[41][54] Manson singled out "Target Audience (Narcissus Narcosis)" as his favorite track from the record and that, to him, it related to every person's desire for self-actualization.[73][55]

Borrowing a riff from English alternative rock band Radiohead, ""President Dead"" is a guitar-driven song that showcases John 5's technical skills.[49] The song opens with a vocal sample of Don Gardiner's "ABC News Radio" broadcast of the death of John F. Kennedy, which is the track's subject matter.[54] On the final mastered sequence, the song is 3:13 in length—a semi-deliberate numerological reference to frame 313 of the Zapruder film, the point where Kennedy's skull exploded from the second round Lee Harvey Oswald fired from his 6.5 x 52 mm Italian Carcano M91/38 bolt-action rifle, and the point where JFK became an American media martyr, "because the production value of his murder was so grand; the cinematography was so well done."[54] "In the Shadow of the Valley of Death" is an introspective song where Adam is at his most emotionally vulnerable, to the point of wanting to give up.[54] "Cruci-Fiction in Space" further delves into the Kennedy assassination, and concludes that human beings have evolved from monkeys to men and, finally, into guns.[32] "A Place in the Dirt" is another personal song characterized by Adam's rumination and self-analysis of his place in Holy Wood.[49]

| “ | "We truly sit in the shadow of death, or rather the billboard that advertises it. We're all going to die... and if enough people are taking photos, we will all be stars." | ” |

| —Marilyn Manson[41] | ||

"The Nobodies" is a mournful, elegiac dirge that begins with a synth-drum and harpsichord introduction.[32][49] The verse "[t]oday I'm dirty and I want to be pretty, tomorrow I know I'm just dirt" is sung with an Iggy Pop-style vocal delivery that builds to the adrenaline-fuelled chorus of "[w]e are the nobodies, we wanna be somebodies, when we're dead they'll know just who we are. Some children died the other day, we fed machines and then we prayed, puked up and down in morbid faith, you should have seen the ratings that day."[9][32][49] CMJ noted that the song was likely to be interpreted by some people as a tribute to the perpetrators of Columbine, but that its point was not to glorify violence; rather, it was to depict a society drenched in its children's blood.[32] "The Death Song" is the turning point for Adam; he no longer cares.[54] Manson described it as being sarcastic and nihilistic: "it's like 'We have no future and we don't give a fuck'."[54] Kerrang! described it as among the album's "heaviest" songs.[49]

In "Lamb of God", Manson uses the examples of the assassinations of Jesus Christ, JFK, and John Lennon to criticize his accusers. He illustrates their hunger for venerating dead people into martyrs and superstars, and for turning tragedy into televised spectacle.[4][56] The bridge paraphrases the chorus of "Across the Universe".[33] Manson notes that even though John Lennon sang that "nothing's going to change my world", "[Lennon's killer] Mark David Chapman came along and proved him very wrong. That was always something, growing up, that was very sad and tragic to me—a song that I always identified with."[33]

Cite error: <ref> tags exist, but no <references/> tag was found

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "N", but no corresponding <references group="N"/> tag was found, or a closing </ref> is missing